- Article

- Read in 6 minutes

The Musical Box – The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway – Live in Montreal 2000

In 2000 the Canadian cover band The Musical Box were the first band who obtained the license to perform the stage show for The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway in Canada. Michael Spuck was there for GNC.

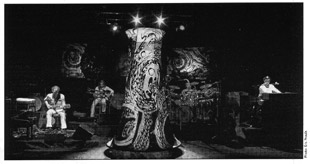

My seat is right behind the mixing desk in the venue, which promises great sound and an excellent view. The Spectrum is a mixture of a pub and a small theatre. There are groups of tables on the floor while on the balcony there are several rows of seats. The stage seems a bit crowded, for the venue feels a bit like a small town venue. There is a simple chair for the guitar player on the left, a little pedestal for the gentleman with the bass and a couple of rocks at the rear end of the stage. Then there is a drumkit with lots of percussions and a stack of keyboards on another pedestal to the right. Everything is ready, it all fits – as we are about to see.

After another musician the light finally goes out at 9:30 and The Musical Box take the stage. The introduction to the story is told by Denis Gagné a.k.a. Rael a.k.a. Peter Gabriel. This already shows how well and true to the original everything has been done and prepared. The clothes, jeans, white t-shirt, black leather jacket, hair-do and the face darkened by make-up – you would notice almost no difference from the famous pictures from 1975. The voice is the same and the gestures imitated perfectly… “This is the story of Rael”.

Eric Savard, the new keyboarder since the summer, has prepared most carefully for The Lamb and begins the first piano runs. There are no digital controllers, no automatic arpeggio – everything is live and manual. The band comes in and Rael begins. Perfect sound. Nicely balance, not too loud, everything is clear – and absolutely floors me. The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway is strong, vocals and other cues are absolutely on time. Rael tells his story without major effects or costumes. The tableau is supported by the first slides from the original set that are shown onto three screens from behind the stage. While reports from the past claim that Genesis would always have technical problems with the show, everything works smoothly here. This is a lack of authenticity I, for one, can live with. Calmer songs like Fly On A Windshield follow after the strong opening number that meets with ecstatic applause.

Rael slips under the keyboards, sings Cuckoo Cocoon lying down, plays the flute and is “stuck in a cage”. This song with its wonderful keyboard solo is another highlight. Beating the tambourine wildly against his leg, Rael seems tortured and forces the mike stand behind his back so that is seems like the bar of a cage. The mike stand allegedly comes from Tony Banks’ basement and had already been used by Peter Gabriel on the Lamb tour. It sure looks old.

A whistle blows, and keyboard chords come in. The Grand Parade … becomes increasingly dynamic – with fascinating drumming. Rael keeps moving around on the stage. Now he stands on a pedestal behind his bandmates, now at the left, now at the right, now in the centre or on the edge of the stage – he is always in motion. It is hard to memorize all the images at the same time while all the slides keep changing in the background. Perhaps this really is one of the first multi-media productions. Rael then tells the next part of the story – he is Back In N.Y.C.. The “bottle filled up high with gasoline” is thrown at the rocks and triggers the first pyrotechnical effect when the small explosion brings on a reddish flame.

A whistle blows, and keyboard chords come in. The Grand Parade … becomes increasingly dynamic – with fascinating drumming. Rael keeps moving around on the stage. Now he stands on a pedestal behind his bandmates, now at the left, now at the right, now in the centre or on the edge of the stage – he is always in motion. It is hard to memorize all the images at the same time while all the slides keep changing in the background. Perhaps this really is one of the first multi-media productions. Rael then tells the next part of the story – he is Back In N.Y.C.. The “bottle filled up high with gasoline” is thrown at the rocks and triggers the first pyrotechnical effect when the small explosion brings on a reddish flame.

Pink hearts appear on the screens for Hairless Heart, the instrumental with this delicate, fragile guitar part where you play along every note in your mind before the orchestral keyboards come in. The performance of Counting Out Time is relaxed as befits the song, and then the atmosphere turns electric for The Carpet Crawlers. The light is dimmed while the song builds up and the audience forms a choir. The guitar solo introduces The Chamber Of 32 Doors; the room shakes when the band comes in. The changes between quiet sensitive parts and stronger bits make this song an outstanding live track. Unfortunately, massive applause covers the final piano chord; one could only hear it if one paid close attention.

The last part of the story is told before Lilywhite Lilith takes care of Rael and brings him into a perfect version of The Waiting Room. The drums come in, there is the rhythm and four strong spotlights blast white light into the auditorium while the shadow of Rael is projected onto the rear screen. A brief piano interlude leads us into The Lamia. The spotlights are fixed on the keyboard while avid helpers fix the “Lamia curtain” at the ceiling. Rael slips in almost unnoticed, the curtain rises (or closes) and the piano begins. The round curtain with the snake pattern on it is alternately lit from the inside and the outside so that Rael is at times invisible or surrounded by the snakes. Blue and green lights make Rael look like a pale ghost in his white overalls. His voice is full of a suffering timbre, and while it fades the guitar solo completes the atmosphere – the Lamia slide off the stage.

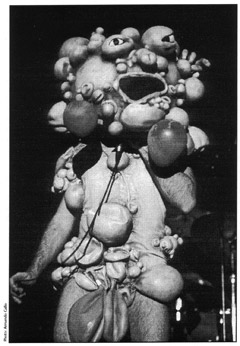

Silent Sorrow In Empty Boats is not as quiet as it should be. Some people are so excited that they are talking rather than listening. This piece deserves more attention. The crew uses this interval to prepare the legendary Slipperman. The rocks at the rear end of the stage split, a slithering transparent tube appears and is lit from behind by a red spot. The Slipperman crawls through the tube like a hatching insect, comes out and stands there in a perfect disguise, shaking its head slightly in time with the beginning. The voice is great, it fits the character, though it does not seem to be easy to get the microphone into the right position under the mask. The inflatable genitals underline what is at stake when Rael gives in to his fate. An absolutely surreal moment. The Slipperman moves across the stage and in a great act of symbolism what was firm before becomes flaccid again. Cured from the Slipperman the glorious times are over. On the screens a raven approaches, comes closer and closer, threateningly, inescapably. It flies away and the Slipperman is gone.

Ravine gives everybody time to breathe before Rael comes back to Broadway. Then there is this maniac keyboard solo in 9/8 before Rael is forced to decide “Here I go.” – and we are In The Rapids. The light is dimmed and focuses on the middle of the stage in preparation for the final blowoff. The keyboard moves up twice and – bang! A flash of light to the left and the right of the stage blinds everybody long enough to make the double-Rael disappear. Mirroring himself he stands on the left and the right and is illuminated by strobe lights. Which one is the real Rael? Back on the stage Rael sums up what It is all about.

Ravine gives everybody time to breathe before Rael comes back to Broadway. Then there is this maniac keyboard solo in 9/8 before Rael is forced to decide “Here I go.” – and we are In The Rapids. The light is dimmed and focuses on the middle of the stage in preparation for the final blowoff. The keyboard moves up twice and – bang! A flash of light to the left and the right of the stage blinds everybody long enough to make the double-Rael disappear. Mirroring himself he stands on the left and the right and is illuminated by strobe lights. Which one is the real Rael? Back on the stage Rael sums up what It is all about.

Contrary to the version on Genesis – Archive 1 the music does not fade out. At the end the synthie plays an ascending note, and with a final bang ends a show that can be called the perfect reconstruction of a work of art. The Musical Box and Watcher Of The Skies are played as encores. Never before have I heard the first song played (and acted out) as well as by Denis that night – that was awesome! It is utterly impossible to do justice to every detail of this show (e.g. the 1,120 slides!) This is a monolith, a complete, full body of art. As far as the music is concerned I have heard many people say that only when they heard the guitar parts on the stage did they realize how important a role Steve Hackett played in composing Genesis songs, and I have to say I agree.

This journey was certainly expensive, but it was an experience I will remember all my life. I also met Paul Whitehead after one of the shows. He had gone up to the balcony during the concert to get another point of view, and he said that while he was walking through the lobby where the sound was slightly muffled and he could not see the musicians it felt like a déjà-vu – had not he heard the same sound 25 years before? I believe him, for he must know.

By Michael Spuck

English by Martin Klinkhardt