- Article

- Read in 46 minutes

Genesis – Why Supper’s Ready may cause an itch

Christoph Laakmann tries his hand at a musical analysis of the prog classic, Supper’s Ready, one of the central pieces in Genesis’ oeuvre.

Musical analysis of a prog classic

[The following text contains scenes of extreme nerddom]

Introduction

In 2022, the interest of rock history got focused on Supper’s Ready with a vengeance: 50 years of Foxtrot! Lo and behold: It was not just prog magazines who celebrated Genesis’ fourth album, which came out in 1972, with its 23-minute longtrack. Even a publication like the German Rolling Stone, an otherwise remarkably strong bulwark against ambitious creativity in compositions, described Supper’s Ready as a “psychedelic masterpiece”. Nobody questions that the pinnacle of Gabriel-era Genesis is a classic progressive rock song.

As a fan of that time, I’ve always taken a special interest in Supper’s Ready. Despite all my fascination with the song and all the cult status it has achieved, I would feel confused and annoyed with some moments of the composition whenever I’d listen to the song. Those very moments sparked the idea of examining the aesthetic substance of the musical songwriting and collection my insights. Combining them in one continuous piece was something I only began to consider when I had the impression that I could add some worthwhile aspects to the essays that have been written about the music of Supper’s Ready so far.

The most interesting piece about Supper’s Ready was penned by Mark Spicer, and it has the slightly cumbersome title of Large-Scale Strategy and Compositional Design in the Early Music of Genesis (2008). I drew on many other publications and sources for important information and inspiration, be they about Foxtrot in particular, about Genesis or about prog music in general. Bernward Halbscheffels song analysis in Progressive Rock – Die Ernste Seite Der Popmusik („Progressive rock – the serious side of pop music”, 2012) and the book Foxtrot (Genesis 1972-1973) – Aufstieg Und Apokalypse by Mark Bell (“Foxtrot (Genesis 1972-1973) – the rise and apocalypse”) were particularly useful. Though I do accept everything they say, they have provided foundations for the content of this essay. I will refer to them explicitly here and there.

I would also like to give you an extensive understanding of the niceties of this composition as well as the piece as one big item of rock aesthetics. Neither in-depth analyses nor personal considerations and focuses can be avoided here. If you want to really say something new about Supper’s Ready after half a century you definitely have to have your own perspective and your own approach for diving deep into the piece.

We will go through it section by section, so we shall examine the characteristics of the seven parts (and three interludes) one by one. After that we will take a closer look at the overall structure and get to possible answers to the question “What is Supper’s Ready, musically speaking?” I only refer to the lyrics if I can link them to the music. If you are interested in backgrounds, analyses and interpretations of the words Peter Gabriel wrote for this piece you can find them easily in other places.

Whenever I mention time codes I refer to the “2008 Digital Remaster and Stereo Mix” of Foxtrot (© 2008).

1. Lover’s Leap – staging a loss of normality (0:00 – 1:57)

1.1 The missing intro

Conventionally we could have expected Genesis to kick off the longest track of their oeuvre with a massive and extensive intro in order to capture the attention and indicate the weight of what is to come. After all, post-Trespass Genesis personify the opulence of classic symphonic prog like no other band. Their intro to Watcher Of The Skies proves that they knew about how crucial the opening gestures can be in a piece of music.

So many intros through the years: The dramatic crescendo beginning of The Fountain Of Salmacis (1971) became the starting point for a whole series of very effectful bombastic openings. Next was Watcher Of The Skies (1972). Its symphonic beginning was a threefold intro to the song, the album, and the live shows. The line continues. Dance On A Volcano (1975), Eleventh Earl Of Mar (1976) and, of course, Duke’s Intro in Behind The Lines (1980) are just the most striking examples. Genesis proved their supreme skill and creativity in this area in that they never even came close to repeating anything.

Now, in their magnum opus the curtain is not drawn with a grand gesture. Alright. They could do it in another way, too, by starting off quietly and delicately. See the atmospheric beginning of The Cinema Show (1973), the mood-setting piano introduction to The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway (1974) and the ancient fairy-tale chords that kick off The Musical Box (1971). Those, too, are significant introductions that had an effect on the whole genre, and they provided very memorable mise-en-scenes for each song.

And in Supper’s Ready? Nothing. Nothing at all. The piece begins without any further ado: “Walking across the sitting room I turn the television off, and suddenly everything goes crazy!” Huh? Not a single note of introduction. Peter Gabriel starts singing with the very first guitar chord. Remarkable as it is, it is not a one-off oddity in the Genesis oeuvre. In fact, they took things to the limit when Dancing With The Moonlit Knight, the opening track of Selling England By The Pound (1973), begins without any instruments and has Peter Gabriel singing a capella.

The beginning of Supper’s Ready proves how versatile Genesis were in writing and avoiding cliché approaches. We also note that the music and the lyrics correspond in that they begin very abruptly. Going medias in res musically was the obvious option for the band; after all, the lyrics do not raise any need for a grand flourish.

1.2 The missing tonic

We need to realize first that, as Mark Spicer points out correctly, Genesis is not a band that is well versed in music theory. Of all the band members it was probably Anthony Phillips who felt the biggest urge to educate himself in this area in the course of his career; of course, he had already left the band by the time Foxtrot came to be. Genesis always composed intuitively and focused themselves primarily on the immediate sonic effect of their ideas and their feeling for the dramaturgy of a song. Incidentally, this applies to every period of their work.

In other words, they were interested in musical structures as far as expressed themselves in a way that directly appealed to their listeners, and also in their connection with the creation of arcs of tension. Especially Tony Banks has always been aware of this. A theoretical analysis of the songwriting – as we can see from several statements by band members – was only important to Genesis when it came to problems of technical realisation of the material.

Genesis may therefore have failed to realise how remarkably rich and unusual the harmonic structure of Lover’s Leap is. Let us examine this by understanding what it means that a piece is written in a certain key signature. The home key is an influential centre of the music, and everybody is aware of it. It gives the process of listening its tonal point of reference – like a kind of home port.

The composition starts from there, moves on in a perceptible relation to it and in most cases also returns to it. All melodies and chords in the song, and all its rhythmic phenomena relate to this centre, which means it is effective at all times. But if you look for the basic key of Lover’s Leap as a starting point that provides stability and orientation for the journey ahead, you will feel like you are playing hide-and-seek in a maze.

Let me say up front that there is not a single second here in which a home key worthy of its name appears. In the first two bars, the music still pretends to refer to the root note ‘e’ (in his analysis, Spicer assumes it is E major, but it could just as well be E minor). At the beginning of bar 3, something happens that is characteristic of the entire part: the music moves away from the tonal centre it is supposedly aiming for – in this case to B minor (0:08). In terms of listening psychology, this means nothing other than a (briefly) disappointed expectation of reception and thus a destabilising moment.

Things continue with more surprising twists and evasive manoeuvres. This becomes particularly interesting when we include the lyrics in our considerations. We have already mentioned the abrupt beginning, which, in view of what has just been said, unites the lyrics and the harmonically exciting, open structure of the music.

You can recognise this not just by the fact that the music avoids moving to the supposed home key after the opening chords, but also from the very first chord: It consists of a-c-e-f sharp and contains strong dissonances (c/f sharp and e/f sharp). In relation to the root note E it clearly belongs in the subdominant sphere, which is a sphere that moves away from the home key (= tonic). Figuratively speaking, the music turns its back on its home port, or the chimera of its home port, from the very beginning and faces the open sea.

Also note the passage where the speaker affirms a sudden change in the face of his beloved (‘I swear I saw your face change’). You might assume that Genesis had deliberately designed the following: As in bars 1-2, the harmony once again seems to move towards the apparent root note ‘e’, but now performs a turn to B flat major (0:22-0:26) with the help of a quick cadential movement parallel to the textual change in the situation – which is at a tense tritone interval to ‘e’!

This is even done quite elegantly and therefore it is very acceptable for the ear: ‘D sharp’ and ‘F sharp’ of the B major chord reached at ‘night time’ become common notes of the following E flat minor chord – you only have to change them enharmonically (i.e. to ‘E flat’ and ‘G flat’). From E flat minor we can reach B flat major via a dominant seventh chord on ‘f’.

This both unusual and very fast in terms of harmonic, thus it perfectly illustrates the equally unusual events in the text: The seemingly reality is suddenly suspended as the supernatural intrudes into the normality of a couple at home.

The refreshing effect of the new, major, key is not that unusual. It simply lives up to the nature of a good chorus, which is intended to take the song to a new, heightened level. What makes this unusual is the fact that the B flat major environment has nothing to do with the previous harmonic area, in which such distant chords as B flat major and F sharp major occurred, and that the music jumps to it so unexpectedly. The shift to B flat major is more than a mere change of atmosphere; from a tonal point of view, it is a real break, a kind of false movement – and it takes place at the very moment when Peter sings: ‘it didn’t seem quite right’. Fascinating!

If you have listened to Supper’s Ready countless times before is unlikely that you will stumble across such harmonic peculiarities; you are more or less used to them. Moreover, the first part has the soothing flair of iconic Genesis folk – with no less than three twelve-string guitars here (and a cello). Their easy interplay radiates something peaceful and unagitated.

Nevertheless, it is perhaps worthwhile to perceive this shift once again, consciously, as if you listened to it for the first time. The conspicuous use of the “wrong” B flat major chord shifts the music into a noticeably different expressive range as it approaches the chorus, which Peter Gabriel also marks with a change in his voice from the words “Hello babe” onwards: The music or particularly the vocals seem clearly artificial – fake. In the live situation, Gabriel supported this impression with an affected swaying of his body.

It is significant that the lyrics of the chorus are an attempt to conjure up the truthfulness of love: “(…) don’t you know our love is true?” Thus, the music transcends the immediate semantics of the lyrics to tell us what is really true: the very thing that is supposed to be unconditional and permanent suddenly turns out to be an illusion that must now be desperately maintained. The request to turn to the (explicitly secular) dinner in the second chorus can be seen as an expression of the anxiety-driven wish that everything to return to normal as quickly as possible.

1.3 An enigmatic prologue

Apart from the missing intro, Lover’s Leap is structured like a normal song: First verse (from “Walking across the sitting room”) – chorus (from “And it’s hello babe”) – second verse (from “Six saintly shrouded men”), chorus (from “And it’s hey babe”), bridge (from “I’ve been so far from here”) – and then it ends. In order to fulfil the traditional pattern (and it musical point) the chorus would have to repeat once more. As a stand-alone song. Lover’s Leap would appear to be incomplete or ending randomly.

In view of what is to come, however, the structure of the first part makes total sense artistically: After all, a large-scale episodic form does not work if the end of a section already conveys a sense of completion. The very incompleteness of Lover’s Leap is therefore necessary in order not to spoil the whole thing of its forward-looking tension. The (rhetorical) question at the end of the last line (“Hasn’t it?”) is the lyrical equivalent of an expectation, which is also fueled by the music: This cannot be the final word.

To conclude: Lover’s Leap overrides what seem to be the laws of composition. What is self-evident is audibly counteracted, not least in the music. The chord arrangement is extremely dense and complex for a rock song. It also remains unpredictable in its progression due to the lack of a real key signature. In the beginning, a conventional song pattern is implied, but does not turn up. The fact that the chorus of all things – the central part of such a scheme – is given a flavour of intentionality and artifice, thus contradicting the lyrics, can be seen as another unusual highlight.

To put it pointedly, the first part of Supper’s Ready is a prologue written as a musical riddle, and it seems to changes all the more enigmatically the closer you look at it. Sarah Hill’s examination of the narrative text structure of Supper’s Ready in her article Ending It All: Genesis And Revelation (2013), is a fitting reference. Hill comes to the conclusion that Lover’s Leap also corresponds to the characteristics of a prologue on this level.

All in all, you would probably have to search music history very carefully to find a more interesting introduction to a rock song.

Interlude 1 (1:57-3:52)

The question of formal cohesion is one of the particularly neuralgic aspects of Supper’s Ready. There is ample evidence that the structure of the work is not the result of a visionary idea or has been planned in any detail. On the contrary, it only developed in the collective process of songwriting under time constraints in a way that the band could not foresee. Mark Bell presented a thorough reconstruction of this process in his Foxtrot book.

However, the fact that Supper’s Ready was composed as if into the blue and that the final running time had nothing to do with initial concepts is no reason to call the long form as arbitrary or even unsuccessful. The process of Genesis gradually creating a whole from building blocks, some of which were created completely independently of each other, actually corresponds exactly to what the term “compose” means, according to its origin: “to put together”.

Genesis decided to link some, but not all of the seven parts with interludes. These interludes went unmentioned in the liner notes. This indicates that they were employed case-by-case and there is no general necessity. Whether they make sense aesthetically is a question that can only be addressed by looking at the concrete piece of music.

As mentioned above, the C section “I’ve been so far from here[…]” turns out to be an abruptly opened exit from the Lover’s Leap prologue. It takes a final (and, once again, unexpected) step towards the Dorian scale by way of the note ‘d’. The interlude that begins at this point remains in the sphere of the beginning in terms of sound: twelve-string guitars once again pluck a pattern of broken chords. In contrast to the unpredictably erratic Lover’s Leap, however, the music now circles back into itself. The previously rapid succession of unusual chord combinations is followed here by an almost continuous persistence on the ‘d’ in the bass and a uniform guitar ostinato. Long vocalizations, a few flute notes and an electric piano solo unfold above this.

It is also clear to hear that this first interlude has a connecting but not a transitional function. Essentially, it can be seen as a meditative echo of the lyric line “It’s been a long long time. Hasn’t it?”. Shortly before the end, Genesis then introduce the beginning of the second part with a harmonic movement towards A minor.

Though the interlude may be credited with sonic charm and an engaging atmosphere, the songwriting does not offer any special treats here. A considerable musical problem, however, lies in the fact that no progressive effect is created after the equally subtle and moderately fast prologue. Lover’s Leap ends where Supper’s Ready should really begin. A retarding moment at this point, shortly after the triggering impulse of a lyrical and musical action, is extremely questionable in terms of the dramaturgy of the form’s progression.

There are further complicating aspects: firstly, this procrastinatory passage lasts just under two minutes, which gives it as much temporal weight as the prologue; secondly, the following part even has a short introduction of its own (“I know a farmer […] after the fire”). Accordingly, a shorter and more focused transition would have been an alternative worth considering. The band could certainly have considered this without having to anticipate the structure of the entire long track.

2. The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man – Attempted deception with a break-off (3:53-5:42)

Almost four and a half minutes into the song we finally get the dynamic impetus that Supper’s Ready could have used beforehand. The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man comes along like a musical main theme (while Lover’s Leap is definitely revealed as the preceding prologue). This is due to a few conspicuous events that take place simultaneously: Firstly, after the narrator’s introductory reference to the strange “fireman” the entire band finally kicks in and with it one of the elementary rock musical elements: the beat from the drum set. Secondly, after a tension-generating crescendo on a dominant seventh/ninth chord, we hear a radiant A major triad. For the first time we get the impression of a real home key (4:23).

Although there have been a few tonal intermediate centers in the music before (in the preceding Intermezzo it was the ostinato ‘d’), none of these centers were musically pegged into the ground as massively as is the case here. In addition, Peter Gabriel underlines the weight of this passage melodically with the drawn-out “You” on the stabilizing fifth of the A major triad, while Tony Banks’ organ cements the triad notes and thus the key like a fanfare.

The eponymous protagonist, who is now up to his lyrical mischief, is branded an impostor right away (“You, can’t you see he’s fooled you all”). Musically, however, there is no sign of this at first: Supper’s Ready progresses almost gravitationally in four time, and every time the name of the Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man is celebrated as a hookline we hear an almost overly solemn chord sequence – as if homage were being paid to a great ruler.

Compositionally, this part is not as spectacular as Lover’s Leap. The gem is the aforementioned chord sequence (accompanied by a fittingly ascending bass line), which is quite original and also has a very expressive, uplifting effect. The music has nothing enigmatic or even ambiguous about it, but shines in triumphant splendor almost until the end. But then the hook line is repeated and it suddenly breaks off: “he’s the guaranteed eternal sanctuary” – oops? Is he not, after all?

This passage (5:28) is,first of all, another attack on the expectations of the listeners, who could not have expected such an abrupt end to the radiant glory. At the same time, it corresponds clearly and meaningfully with the promise of eternity (which must possibly be read ironically) that is attached to the supposed saviour: this now also proves to be an air pocket musically.

After the break-off, a pale, dissonant organ chord comes in and suggests that the music that was previously so majestic is now more likely exposed as a lie. You cannot hear it immediately, but this initially irritating organ sound is not an arbitrary sound. Its notes of c, e and f sharp contain almost all the notes in the opening chord of the Lover’s Leap reprise that now follows – only the ‘a’ is missing. In other words, thought the children’s sing-song “We will rock you rock you little snake” is in an unclean D major, it already marks the tonal sphere of the second interlude. The simple melody of the children (six-note range), however, can easily be heard as a musically disarming antithesis to the exaggerated pathos of the full-bodied seducer…

Interlude 2 (5:42 – 6:08)

Like Interlude 1 before it, the second (much shorter) interlude has no progressive character at all. The increased dynamism of Part 2 is quickly over again, and we fall back into Lover’s Leap territory – as if a reset button had been pressed. At least it’s fitting that The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man turned out to be a misleading episode with a sharp break-off point. The couple from the prologue, who apparently embark on a kind of psychedelic-spiritual journey in Supper’s Ready, find themselves back at the beginning, as it were.

Another effect of referring back to the prologue is, of course, that it establishes the impression of coherence. The episodic structure of the long track must not hide the fact that Genesis had a few tricks up their sleeve in order to create the overall feeling of coherence.

On the other hand, the turnaround to Lover’s Leap once again blocks the forward movement of the song, which has only just got going. Tthat the first six minutes of Supper’s Ready feel like slightly depressing stop-and-go traffic on the first section of a longer journey.

3. Ikhnaton And Itsacon And Their Band Of Merry Men – Euphoria for War (6:08-9:37)

With the acceleration effect of the lyric “Wearing feelings on our faces while our faces took a rest” and the start of the drums, the beginning of the third part promises more forward momentum. And indeed, after a short time, Ikhnaton And Itsacon And Their Band Of Merry Men builds up into an expressive up-tempo groove, which is characterized by the martial-sounding use of the snare drum and an optimistic D major (6:33). In a higher vocal range, Peter Gabriel sings about a victorious battle. Tony Banks plays around the groove on the organ with lively melodies and Steve Hackett contributes a rocking guitar solo that he seems to have come up with on the spot.

There is no sign of particularly sophisticated songwriting in this part, though, which is likely to have emerged quite directly from a joint “one-chord jam” (Spicer). It’s uncomplicated straightforward attitude does a whole lot of good to the musical development of the song. In addition, the bold exuberance and cheerfulness match the lyrically less-than-complex depiction of the war episode, which almost reads as if it were a children’s game: “Bang, bang, bang…”

There is a reference to “a wonderful potion”, which seems to ensure that the warriors can carry out their bloody business without any emotional concerns. The terrible consequences of the events, however, are not even hinted at in this part, neither lyrically nor musically.

Hackett’s solo contains energetic, often upward-striving lines that are in keeping with the expressive level of this episode. It adds a great liveliness thanks to fast passages and a lot of melodic variety. You can also hear that the timing and phrasing do not reach the level he would achieve later on.

Mark Bell rightly notes that the inserted break at the end of the solo is a musical highlight (from 8:03). The accompanying guitar vamp and the drums pause here (except for the hi-hat). Thus they bring a magical little motif into the forefront that essentially consists of broken triads and is repeated by Hackett and Banks in parallel polyphony and then sequenced upwards. It is not only Hackett’s solo that culminates in this tapped passage, but the entire expressive content of the third part. With a view to the lyrics, we might say this is precisely the moment when the war comes to a victorious end from the speaker’s point of view.

When he returns to the jam groove, it makes good sense for Collins to drop his snare drum that made such a ruckus: The military actions is over, things have calmed down. The fact that Tony Banks takes the little triad motif from the break and lays it over the vamp as a cheerful echo of the battle is a delightful idea that favors the inner cohesion of the whole.

It all ends with a convincingly composed decrescendo in which both the instrumentation/sound and the thematic material are carefully thinned out. The end of this section is supported in the very last bars by a subtle, almost imperceptible ritardando. The lyrics previously made us aware that there was to be a victory celebration. Once more, the complex and flexible interrelationship between music and text becomes clear in a very striking way. The music also fulfils a narrative function: It is the music alone that now indicates that the throng of warriors (and thus possible festive activities) is moving away and a scene like an abandoned battlefield emerges.

An interlude? No such thing! How Dare I Be So Beautiful? emerges calmly and organically from the end of Part 3 using a cross-fade technique. That’s another approach.

4. How Dare I Be So Beautiful? – War dysphoria (9:38-11:02)

The fourth episode of Supper’s Ready is the shortest and simplest. Our couple have reached the abandoned battlefield. Although the lyrics speak of “chaos”, it is a ghostly and – as the music conveys – silent chaos of what remains of the war. The two travellers climb a mountain of human flesh, only to find, strangely enough, an natural idyll on its summit. The setting of the text is therefore characterized by a stark contrast.

The music is extremely calm, reduced and highly repetitive. A basic tension is created by the (moderately) dissonant accompaniment of an audibly alienated piano, which is formed from two alternating pairs of chords. Peter Gabriel sings a melody with a small range over it. Supper’s Ready is once again static – even more so than elsewhere – and has certainly reached its sonic-resignative low point with this part.

With this sparse instrumentation, Gabriel’s vocals are naturally the undisputed centre of attention. He shapes this section with his sensitive and, for all his restraint, expressive way of declamation of the text – among other things through a flexible shaping of the vocal color.

If we examine the relationship between music and lyrics, we may say that it is probably the aspect of death and destruction that is echoed in the music. Only the melodic “full of life”, which breaks out somewhat upwards, can be heard as a weak (because it is sung in a very tortured way) reference to the natural scenery in which the couple now find themselves.

All of this subsequently counteracts the amazingly euphoric image of the battle painted in Part 3. Once again – as in the first two episodes – you wonder what is actually reality and what is just appearance, what is truth and what is deception. The songwriting of Supper’s Ready is characterized not only by strong contrasts, but also by the principle of questioning and reversing supposed factuality. In purely musical terms, this principle can be found in the harmonic, melodic and other formal breaks as well as the strongly contrasting changes – in other words, in a constant relativization and destabilization of the reception process.

It is very a very apt observation in these considerations that at the end of How Dare I Be So Beautiful? there is once again a question mark – both a textual one (“A flower?”) and a musical one, as the harmony finally makes an evasive movement to the unspecific fourth f sharp b, which comes completely out of the blue – and bring on a general pause. As a result, this ending simply hangs in the air.

This fourth part seems coherently composed in terms of its basic conception if you consider that the principle of extreme musical reduction creates a successful and significant antithesis to the battle action of the third part. Musically, it is an almost lifelessly rigid moment that fits very well with the harrowing image of the mountain of corpses. The lyrical contrast of the green, overgrown summit is reflected just as little in the musical expression as it was in the brutal violence of war in the previous part.

There is, however, peculiar constellation of figures on the plateau: there is a human bacon sitting still by the pond, and this bacon is, absurdly enough, us listeners, and also Narcissus in metamorphosis. When the unexpected quartal conclusion rings out as the musical equivalent of the final question mark (“A flower?”) it reflects only Narcissus.

However, Peter Gabriel’s well-known accompanying text to Supper’s Ready reveals that these different (id)entities merge in the figure by the water. Before that, the music remains in its joyless chord loop, which doesn’t bode well for the mindset of the figure(s), but doesn’t give the events on the mountain much area of expression either.

To conclude, Parts 3 and 4 are in many respects a contrasting pair. This is all the more striking as the location of the action, i.e. the battlefield, is the same in both episodes. It has merely transformed. Like Narcissus changes. And then everything in general…

5. Willow Farm – Orgiastic Eccentricity (11:02-13:35)

Tony Banks had the brilliant to attach this fifth part, which Peter Gabriel originally intended to be a stand-alone song, straight to the very restrained How Dare I Be So Beautiful? without any interlude. It creates another enormous contrast. The energy that Willow Farm generates through this contrast as well as its exuberant and ever-increasing eccentricity obviously provided the decisive impetus for the band to continue the songwriting so that the last two episodes came about relatively quickly.

Up to this point Supper’s Ready was a puzzling game with perceived realities and perceived identities and their possibility to morph and transform. Now this game is taken to extremes in an almost childishly uninhibited manner: “The frog was a prince, the prince was a brick, the brick / was an egg, and the egg was a bird (…)”. Lyrically, Willow Farm fits in amazingly well with the concept of Supper’s Ready so far.

Musically, it is a different story, as it is (as most parts are) compositionally completely independent that does not reference any of the thematic material of other episodes. Its clear three-part structure A-B-A’ is almost classical and appears self-contained. This makes it particularly different from the first two parts.

However, a small compositional trick prevents the impression that the end of this fifth part might also be the end of Supper’s Ready. Compare the opening and closing turns of Willow Farm: Everything begins with a rhythmically pounding downward motion (E flat, D flat, C flat, H flat), aiming for the note ‘A flat’ as the new root note of the key of A flat minor (alternatively also ‘G sharp’ and G sharp minor – in any case, it is the most unusual key of the entire long track, which of course suits the exalted character of this part). The deeply altered second degree (heses) is worth noting here, as it strikes a Phrygian tone (even if this is immediately withdrawn afterwards).

At the end of Willow Farm (from 13:33), this downward movement is heard a third and final time – only the conclusion is no longer the expected root note (i.e. ‘a flat’ or ‘g sharp’), which would have given the impression of completion, but the ‘g’, which is a semitone lower (so that the previously lowered second step ‘heses’ can be heard here retrospectively as ‘a’), as well as an additional low ‘c’ in the bass.

The resulting surprise effect is another subverted (here: tonal) auditory expectation at the end of a part. The resulting uncertainty suggests a continuation of the piece. In addition, the final downward passage and the movement that comes to a standstill on the empty fifth ‘c-g’ in the lower register can be heard as a musically meaningful representation of the preceding lines of text: Everything there finds its final place deep in the ground.

The grotesque orgy of transformation leads to a dark end-time scenario in terms of both sound and lyrics and is therefore unlikely to be received as a positive utopia. On the contrary: its conclusion can be seen as an unsettlingly fundamental questioning of the principle of identity (and therefore also means an intensification of identity problem the lovers have) – especially as the essential changes to all things and all living things do not occur of their own accord, but at the command of a shrill whistle, and the final burial of the previously exuberant, hidden picture is accompanied by a seemingly violent bang. The tonal gender of the framing A section (in minor, too!) does not exactly create an atmosphere of light-hearted activity either.

Willow Farm is a rather unusual pop song, the sound of which has some retrospective characteristics of music from the British sixties. These can be heard particularly well in the B section from “Feel your body melt” onwards. However, its complexity and hook-free structure demonstrate the musical paradigm shift that progressive rock brought about around 1970. Apart from the strange key (which surprisingly changes to A flat major in the B section directly after “All change”), there is a high density of unusual chords and chord progressions, including chromatic bass movements, which provide a lot of color, liveliness and unpredictability.

This is complemented by various irregular sectional formations and time changes as well as the patterns in the accompaniment that keep changing. There is a fundamental metrical change from the A section (ternary beat) to the B section (binary beat) and back again. Shortly before the return to the A section, a single bar of 5 (“Momma I want you now”) is suddenly inserted as a somewhat bumpy break. In addition, there are all kinds of acoustic alienation effects and vocal passages that make the music seem over-excited.

Although this part has a lot to offer in terms of humour and entertainment, it certainly doesn’t belong in the category of light entertainment despite its characteristics. It also clearly differs from the structurally simpler pop aesthetic of the 60s. As striking and original as Willow Farm is stylistically, even appearing a little like the (highly welcome) bird of paradise in Supper’s Ready, the content and sound level work together remarkably harmoniously to create an grotesque episode.

Various parties, including the band itself, have noted that in this respect it also represents a stylistic link to the similarly very British Harold the Barrel from Nursery Cryme. It should be added that Willow Farm is even more artistically distinctive due to the more unusual lyrical and musical (including studio) means employed, thus demonstrating an evolution

Interlude 3 (13:35-15:35)

This last and quite extensive interlude has a clear two-part structure. The first part (until approx. 14:15) takes the drawn-out final fifth of Willow Farm as its nucleus and is therefore still directly related to it. However, because the heavy, sombre music initially loses its rhythmic and melodic activity completely, nothing remains of the colorfulness and liveliness of what has preceded it and actually changes into its exact opposite – typical Supper’s Ready! Now there are deep sustained sounds, to which Steve Hackett adds a few drawn-out, ghostly tones. After a few seconds, the eerie atmosphere is heightened by enervatingly repetitive bendings whose alarmist gesture bodes disaster.

The second part of the interlude, the beginning of which simply overlaps the final note of the first, initially reduces the musical events to a delicate guitar accompaniment in A minor. A little later, a simple, absent-minded flute melody can be heard above it. It is repeated twice, while the chordal accompaniment grows richer and thus varied by organ and later another guitar. The melody finally seems to be repeated for a third time, but after a short time (at 15:30) it takes a surprising upward turn, and with the help of a completely unexpected suspenseful dissonance (a shortened dominant seventh chord on ‘c sharp’), the interlude is then transformed into the spectacular next part: the Apocalypse in 9/8.

If the musical functionality of the first two interludes was not exactly unproblematic from a formal point of view, Genesis’ intuition was spot on at this point: Shortly before the dramatic climax of Supper’s Ready, a retarding moment is certainly appropriate.

There may be different views about whether it is right to introduce a completely new theme with the flute melody or whether a motivic return to a previous motive would have made more sense here in order to give the long track more coherence. There is, however, much reason to prefer the solution Genesis chose: it is precisely because the wistful flute melody marks a completely separate place (that has no connection to the rest of the piece) that this passage is given a particular position within the dramaturgical development.

The catastrophe that follows has already been foreshadowed (at the latest) in the first part of the interlude. Directly before the apocalypse, however, Genesis interrupt the course of events in an almost escapist manner and creates the impression that there is still a musical island that is completely remote in the truest sense of the word and thus apparently the hope of escaping the approaching disaster after all. The effect of the apocalyptic visitation is all the more powerful.

6. Apocalypse in 9/8 (Co-Starring the Delicious Talents of Gabble Ratchet) – In the beat of apocalyptical chaos (15:35-20:43)

Not just the time signature of this part is unusual, but also the fact it is mentioned in the title. This probably diminishes the menace of the concept of an apocalypse just as much as the fact that it is added in brackets. It should be noted that Tony Banks, the musical initiator of this episode, planned early on to integrate humorous elements into the music. Apparently, the band did not intend to go over the top all deadly serious.

Incidentally, the part does not begin in 9/8 time, but in 9/4. The reason: Phil Collins first plays a bass drum running in quarters, which continues the basic beat of the 4/4 beat in the preceding interlude. For the time being, the quarter pulse of the music therefore remains constant. In addition, the first chord change (15:41) occurs after nine crotchets, creating a clear metric focus. At his point we can hear precisely nothing of the 9/8 sequence (e, e, f sharp, e, b, e, e, e, f sharp) that will subsequently accompany the part as an ostinato. In short: There is no musical event in the first bar that indicates a new bar after nine quavers. Nor does the guitar, which runs through in repetitive quavers.

After nine quarters, the aforementioned ostinato begins on the guitar. But even now, there is still no obvious 9/8 groove. Collins continues to kick the bass drum in quarters, there is still a gap of nine beats between the striking chord changes, and the 9/8 ostinato is relatively quiet in the mix. Nevertheless, from this moment onwards, we can speak of a polyrhythmic constellation.

It is only when the vocal part has ended before the long organ solo that the 9/8 time (from 16:12) emerges clearly and takes the lead. Collins now incorporates the snare drum into his playing and begins to adjust his groove to the guitar ostinato. On closer inspection, you will discover the metric change beforehand, namely in the lyric: “(…)You can tell he’s doing well, by the look in / human eyes / You’d better not compromise. / It won’t be easy”. This is the first time there is a chord change after nine quavers (16:09).

The Apocalypse in 9/8 does come in all of a sudden from a rhythmic point of view. Genesis actually create an extremely delicate transition from 4/4 (at the end of the interlude) to 9/4 (in the beginning of part 6) and then proceed to overlay the 9/4 beat with 9/8 structures (i.e. the guitar ostinato and adapted chord changes) until the 9/8 beat is finally established and has arrived in the listener’s consciousness. There is hardly another band in early 70’s classic prog who could have composed such a transition in such a naturally flowing way.

The organ solo begins after a striking harmonic turn to E major and confirms this key with the very first notes. However, Tony Banks quickly detaches himself from the major scale and makes very intuitive use of the diverse tonal possibilities the ostinato offers him, an ostinato that consists of just three different notes (e, f sharp, b). The rhythm of the solo also clearly does not follow a detailed plan or a fixed time signature. Banks himself has said that he actually deliberately ignored the 9/8 accompaniment so that he could shape his solo independently of it and rely solely on his keen sense for effective tone and chord sequences. The result is an unbound, chaotic but very lively polyrhythm with two clearly calculated dramatic climaxes – not at all inappropriate for an apocalyptic scenario.

As Johan Steensland correctly points out in his analysis ‘Genesis Apocalypse 9/8 rhythms [sic] explained’ on YouTube, Banks initially even plays a waltz rhythm with his first notes. The solo thus begins in the manner of a dance (in the bright kay of E major) while the lyrics conjure up doomsday. With this, the solo undermines the horror of the lyrics in a grotesque manner.

Banks leaves the major sphere as quickly as the waltz step, although he retains something of the dance-like element at first. As the solo progresses, various sections are strung together, some of which are melodically original and concise, but some of which are very uniform in motive and even etude-like. For example, the second major climax (from 18:13) before Gabriel’s vocal entry consists exclusively of almost pedantic sequences of identical quaver figures, which simply rise step by step. If you only heard the organ here you would certify an almost disturbing lack of imagination to Banks.

We don’t hear only the organ, though. And the very uniform passages of the solo draw attention to this observation: The appeal of the music here is essentially generated by the interplay of several factors. Banks can string together as many simple figures as he likes in a four-note meter, as long as the 9/8 ostinato runs underneat we get an ever-changing pattern of accents and intervallic relationships emerges.

Then there are the drums. Their importance for the magnificent effect can hardly be overestimated. Ultimately, it is Collins who (after initial difficulties during the first rehearsals) becomes the important link between the 9/8 riff and the solo. In the beginning, he plays along and associates himself more with the ostinato. He comes to detach himself from this, though, weaving in more and more off-beats and fills that enrich and intensify the solo and especially its progressions.

In some places, the drums correspond very closely with the melodic gesture of Banks’ organ figures and make a point of their support role, while in others Collins uses the resulting space and unleashes a rather contrapuntal dynamic. The fact that he can do this so unerringly is, of course, due to the fact that the solo is not at all improvised, but follows a fully composed course.

We know that Tony Banks originally intended the climax of Apocalypse to be the dramatic chord sequence he plays after the aforementioned final build-up of the solo. At the end of this long build-up, he cleverly places a short sequence of alternating octaves on ‘c’ (18:45), which have an intensifying effect due to the dissonances created (to the ‘f sharp’ and ‘b’ of the ostinato) and also prepare the following C major triad in the right hand.

Peter Gabriel threw a spanner in the works and unexpectedly sang his “666 is no longer alone (…)” over the prepared chords. Banks’ anger evaporated after a few seconds. He quickly realized that Gabriel’s highly expressive vocal use pushed the peak of the drama to an unimagined level. In addition, especially the passage “In blood, he’s writing the lyrics of a brand new tune” created a delightful connection between text and music. Banks initially oscillates back and forth between the chords of C major and D major. Combined with the ostinato that continues to run through has E as its central note this gives the impression of the key of E minor. In “brand new tune”, however, Banks creates a lightning-like brightening with an unprepared E major chord, thus emphasizing the impression of a new mood. This moment on its own is an extremely effective turning point.

We should remember, though, that Banks already employed the E major range at the beginning of his solo (and in several subsequent passages). In a wider context, the harmonies of Apocalypse are by no means taken into a new area, but , as it were, back to their beginning.

Still, the final shift to E major has something liberating and freeing about it. Banks confirms this in the following bars by still playing weighty chords that now descend and relieve the tension. At this point, one could rightly say that the musical apocalypse has come to a clearly perceptible end. Accordingly, the pulsing movement of the music – and thus also of the long ostinato – comes to a standstill shortly afterwards in B major.

However, we have not yet reached the final part, the triumphant musical resumption of The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man episode. Before that, a short reprise of Lover’s Leap appears out of nowhere. From a harmonic point of view alone, this is not a marginal note. Within the space of a few bars, the music now performs a beautifully quick movement from the aforementioned B major: first to the distant B major of the Lover’s Leap refrain, then via its parallel key of G minor back to the crossover area to the A major of the concluding As Sure As Eggs is Eggs (Aching Men’s Feet). Running such a zigzag course across the circle of fifths is a very hard nut to crack and it will very probably sound artificial and awkward. With Genesis it sounds natural, as if if could not be any other way.

And the effect of this movement? The harmonic distances that are bridged at great speed and the return to the Lover’s Leap prologue give the impression that we are moving far away from Apocalypse in 9/8 in no time at all. The musical persuasiveness benefits from this. A direct switch from the catastrophe scenario to the redemptive hymn of the last episode could have seemed supremely uninteresting. While Genesis had not shied away from creating harsh contrasts and breaks several times before, here they demonstrate their feel for the unique nature of each artistic moment.

7. As Sure As Eggs is Eggs (Aching Men’s Feet) – A Major for all eternity (20:43-23:06)

A reprise is one of the most obvious ways to bring a longer composition to a musically meaningful conclusion. It creates and arc whose end explicitly refers to the beginning. There are several prominent examples of this in the increasingly expansive structures of experimental rock music around 1970, take, for example, an influential long track like Pink Floyd’s Echoes.

Supper’s Ready is also rounded off from returning, as it were, to the beginning of the piece. Nevertheless we need to remember what we already observed considering the end of Apocalypse in 9/8: For the finale, Genesis did not resort to the first but the second part, whose status as the main musical theme is thus confirmed (while the previous – much shorter – reprise of the Lover’s Leap episode underpins its prologue function). Once again, it is pointless to speculate about the degree of intuition or reflexion the band brought into this decision. Musically, it can certainly be justified.

As Sure As Eggs is Eggs (Aching Men’s Feet) now evokes the A major key of The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man, bringing us full circle harmonically: It is, after all, the first truly established key of the whole piece of music. (The 1973 Supper’s Ready recording from Shepperton Studios shows that Genesis did not consider the unity of the tonal framework to be an absolute aesthetic necessity: the song is transposed down a whole tone before the Lover’s Leap reprise, so that the last part is in G major).

The last lines of the lyrics show prove what has been confirmed from other sources, too, namely that Peter Gabriel was thinking about the victory of good over evil in these lines. Compared with part 2 the mood is hymn-like and almost apotheotic. The music now seems even more solemn as the tempo has slowed down, the beat confirms this solemnity. Collins reinforces the gravity of expression in some places with crashing cymbals on the backbeat. Added to this are the orchestral Mellotron, the enormous intensity of the vocals and, of course, Hackett’s glowing jubilant phrases on the electric guitar, which sounds with a lot of sustain.

If you pay attention to the instrumental accompaniment, you will notice an ostinato triplet rhythm on the note ‘a’ (Rutherford seems to play it in the middle register on the guitar, and Banks perhaps, too, in his right hand) which is consistently maintained even over the characteristic chord sequence with the ascending bass line (‘Like the river joins the ocean[…]’).

Looking back at the harmonically extraordinarily complex and unstable nature of the beginning of Lover’s Leap’s, it seems as if the band is doing everything it can to achieve the exact opposite effect: The very massively staged target key of A major (including the stubbornly repeated root note) conveys rock-solid unshakeability, thus overriding the conceptually very effective motifs of deceptive appearance and transformation. This is accompanied by the idea of a new spiritual home conveyed in the lyrics: the new Jerusalem proclaimed from above, which now meaningfully replaces the original hook line ‘He’s the guaranteed eternal sanctuary man’.

It is at least as significant that the musical redemption event is not relativised, contrasted or even counteracted at any point, even apart from its tonal solidity. Everything ends unbroken with a fade-out that does not set a final point but suggests infinity. This results in two further references:

1. The fadeout can be read as a counterpart to the sudden break eat the end of the part 2, which seals the demise of the seducer who has taken up the cause of eternity.

2. The irrevocable effect of the triumph of As Sure As Eggs is Eggs conveys that the diabolical chaos of the apocalypse in 9/8 has been overcome for good.

However, this raises the question of the aesthetic credibility of the finale. Its undisputedly radiant victorious pathos does not easily fit in with the notorious ambiguitiy that has characterised Supper’s Ready up to this point. In the overall context, the seemingly unproblematic resolution of all areas of tension smacks strongly of a deus ex machina.

Mind you, it is the musical level that never questions the simplicity and unbroken nature of the final triumph. The lyrics are much more complicated. Mark Bell points out a whole series of enigmatic allusions and intertextual references Peter so enjoys making. They not only make interpretation an astonishingly complex undertaking, but also enable readings that question the apparent religious seriousness of the episode in an ironic way. However, the music does not correspond to this.

As a consequence, it can be said that As Sure As Eggs is Eggs (Aching Men’s Feet) can be regarded as a suitable conclusion because this reprise of the second part, which is noticeably more expressive, has a clear final effect and creates a high degree of coherence. In terms of sophistication and subtlety, however, the music comes second to the text.

Conculsion: Sum Of The Parts

One thing should have become clear from the previous analytical observations: although the final form of Supper’s Ready was created under rather adventurous circumstances, the criticism which has been raised repeatedly, namely that Genesis have created a seemingly random series of individual parts or even a patchwork item can be rejected for good reasons. The longtrack features a multitude of meaningful relationships between the episodes and also contains several elements that hold the whole together.

In the overall dramaturgy of the musical progression, the first two interludes are problematic in terms of their function and effect. Apart from this, the result is a harmonious series of musical contrasts that create a convincing arc of tension: The abrupt beginning of the prologue (Part 1) develops an immediate musical and narrative dynamic. Their direction is initially hard to assess and ends like an unsolved riddle. Fittingly, this is followed by the heavyweight main theme (Part 2).

Loose, uncomplicated euphoria (Part 3) is followed by the dysphoric low point of the whole piece (Part 4) roughly in its middle. After a rough turnaround, an agitated grotesque (Part 5) can be heard with increasing eccentricity. Before the subsequent catastrophe (Part 6), the dramatic climax, a suitable retarding moment is inserted (Interlude 3), which allows the force of the apocalypse to emerge all the more effectively. The concluding part 7 develops a tension-relieving, liberating final pathos on the one hand, while on the other hand, as a reprise of part 2, it is a return to the main theme. This also gives Supper’s Ready a cyclical structural component.

A Suite?

The form of Supper’s Ready is repeatedly associated with the ‘suite’. If one sticks to the classical minimal definition of this term, it would be a sequence of self-contained individual movements that are subject to a unifying design idea. In past centuries, this idea was often based on the simple fact that the (dance) movements were in the same key. The perceived harmony of a suite could arise from the fact that the different characters and forms of the individual movements resulted in a complementary, varied overall appearance, revealing the artistic variability of its creator.

If we call Supper’s Ready a ‘suite’ or ‘rock suite’, we can emphasize the compositional independence of the parts and their common reference level, the lyrical context. It is not important to apply an established name to the the form of the Genesis classic. The rough structural idea of the song, however, has nothing inherently deficient about it.

If we want to call it a suite, we must not ignore the peculiarities of the musical progression of Supper’s Ready. The parts are not self-contained but merge into one another – sometimes by way of interludes. In addition, there are episodes that seem incomplete (Lover’s Leap) or abandoned (The Guaranteed Eternal Sanctuary Man). Last but not least, the musical reprises work against the impression that this is merely succession of independent parts. Take all this together and the band’s efforts to overcome the isolation of the parts and instead achieve conceptual unity become clear.

Nevertheless, it is worth taking another look at the individual episodes in their entirety, as they show an impressive variety of styles and thus illustrate the wide range of possibilities of expression that Genesis had already gained as songwriters at this time.

The individual parts – a summary

Part 1:

Iconic Genesis folk-prog with an unusually complex mesh of broken (12-string) guitar chords; missing root key; unfinished verse/chorus scheme

Part 2:

contemporary bombast rock in A major with a short introduction of its own; two-verse (each with final hook line); surprising break at the end

Part 3:

free form with short introduction; percussive euphoric one-chorus jam in D major with electric guitar solo in the centre and composed fadeout at the end

Part 4:

instrumentally reduced arrangement: lead vocals (low range) over resigned four-chord vamp of an alienated piano; slow tempo; harmonically floating (reference key: G major); three-verse with abrupt ending or unexpected harmonic swing

Part 5:

over-excited, over-complex parody of 1960s pop; classical three-part structure (A B A’); increased use of studio effects for sound alienation; eccentric key (A flat minor / A flat major / A flat minor); ending with harmonic deviation (‘g’ instead of ‘a flat’)

Part 6:

free and emphatically progressive form over 9/8 ostinato with central organ solo between two vocal parts; polyrhythmic in places; tonal reference point: ‘e’; attached Lover’s Leap reprise

Part 7:

Resumption of Part 2, but at a reduced tempo; increase in the bombast effect (= effect of a finale); end with solemn electric guitar solo and fadeout; particularly forcefully consolidated A major as the final key

It is easy to see that each part has an unmistakable compositional profile (the relationship between Part 2 and Part 7 constitutes an exception). The spectrum of expression for the listener is correspondingly colourful and promotes the listener’s idea of a journey through a wide variety of scenes, each with its own unique mood.

The overview also shows that it would be too short-sighted to regard Supper’s Ready as the sum of the band’s previous work. The opening Lover’s Leap (including the subsequent interlude) is certainly still in line with the Trespass phase, which produced a folky style of prog whose formative significance for the genre is rather underestimated. Parts 2 and 3 also drew on expressive means that Genesis already had in their repertoire, namely the bombastic rock of the early 70s that was not only typical for them – including longer solos. The long tracks on Nursery Cryme (1971) were the main discographic predecessors.

However, the alienated piano sound in How Dare I Be So Beautiful (Part 4) is the first sign that the course of Supper’s Ready documents a further development of Genesis. The many vocal effects and other sonic gimmicks in Willow Farm make it clear that Genesis were now incorporating the possibilities of studio technology directly into their songwriting. If you want to follow the idea that Supper’s Ready manifests the transition from the acoustic to the electric Genesis, this aspect should be included.

The more experimental tonal language of Apocalypse in 9/8 also represented new territory for Genesis, which cannot be found on earlier albums. Several instrumental parts or keyboard solos were created later in this area, each characterized by a special rhythmic constellation: for example in The Cinema Show (1973), Riding The Scree (1974), Robbery, Assault & Battery (1976) or the end of Dance On A Volcano (1976).

Last but not least, the seemingly compelling linking of the parts in the second half of the longtrack shows an increasing maturation of the band in structural terms. In particular, the dramaturgical structure from Willow Farm onwards is both spectacular and extremely coherent. Conversely, however, this means that Supper’s Ready is not quite woven very tightly and organically.

Moreover, not all episodes have an equally high artistic level. Lover’s Leap, Willow Farm and Apocalypse in 9/8 in particular stand out in a positive way. In terms of the formal perfection and consistent quality of the individual parts, however, Yes had more success with Close To Edge (1972).

A personal remark at the end: My diagnostic curiosity to recognize what exactly it was about Supper’s Ready that had me irritated from the very beginning led me, during the creation of this work, to a constantly renewed amazement at the wealth of details that are not only interesting in themselves, but also constitutive for the overall context of the piece. Contrary to the skepticism that can be brought to bear on an analytically dissecting approach to music, I went through a process of understanding that benefited my reception of the whole. In this process, for example, my earlier astonishment at the immediacy of the beginning of the piece disappeared. I now consider the lack of an intro to be actually particularly successful.

The interludes 1 and 2 will probably continue to make me itch every time for the reasons mentioned above. And the finale definitely lacks a musical barb, a counterpart to the subtle lyrical allusions.

However, the exceptional position of Supper’s Ready in Genesis’ oeuvre and in the history of progressive rock music remains in my opinion due to the many qualities and the profound effect of the song.

Author: Christoph Laakmann

English by Martin Klinkhardt

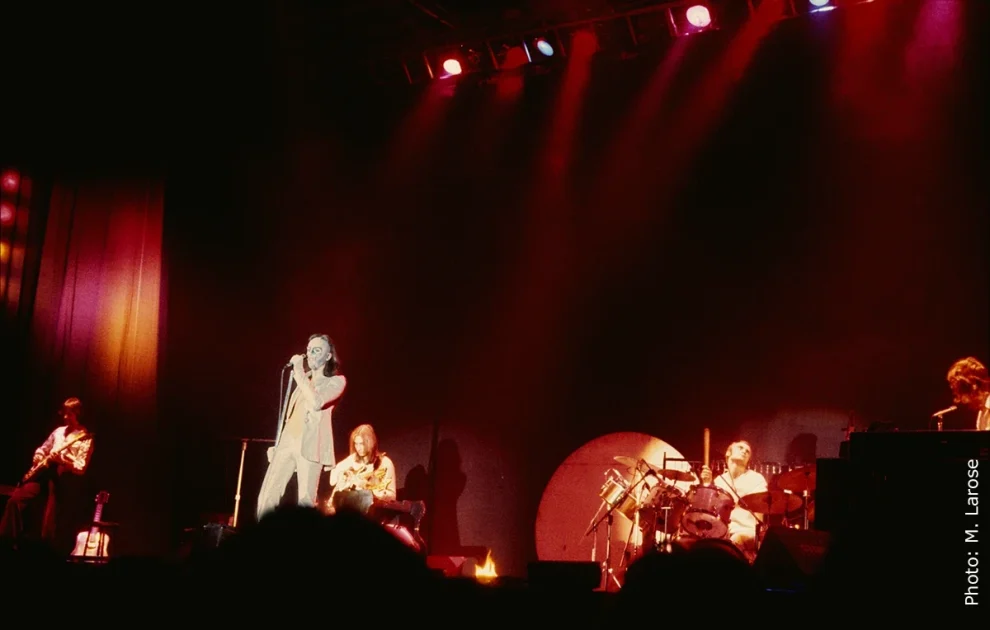

Photos: see images / Screenshots of the 4k Shepperton-Film

Discuss this article and Supper’s Ready in our forum in this thread.

Links:

Genesis: Foxtrot (Review)

Mark Bell: Foxtrot (Aufstieg und Apokalypse) – book review (German)