- Artikel

- Lesezeit ca. 10 Minuten

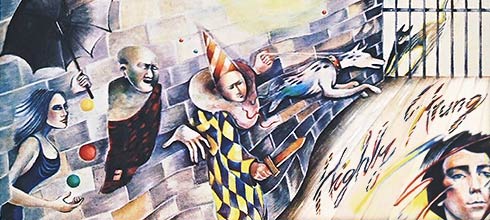

Steve Hackett – Highly Strung – review

In 1983, Steve Hackett released his freshly recorded studio album Highly Strung. Many fans were rather critical of the new rock sound, but musically the album is in no way inferior to its predecessors. Ole Uhtenwoldt took a closer look.

In 1983, Steve Hackett released his freshly recorded studio album Highly Strung. Many fans were rather critical of the newer rock sound, but musically, the album was not inferior to its predecessors.

After many successful progressive solo outings since 1975, Steve Hackett decided to put more emphasis on a rocking backdrop for his sixth solo album. And indeed, Highly Strung differs from its predecessors in many ways. It is no longer quite as versatile as, for example, Please Don’t Touch was at the time, but still combines a number of elements that are Steve Hackett trademarks. And so – without a doubt – the album can also be easily identified as one of his.

Highly Strung not only stands for an arrangement in which comparatively little emphasis is placed on the progressive elements, concept or flowing transitions. It also marks Steve’s last solo album released on the Charisma label. The sound is less expansive, but benefits considerably from Steve’s various guitar interludes, which are again top-notch on this album. From a purely musical point of view, the whole thing is relatively song-oriented, but you can see Steve’s stylistic diversity, because the rock part of his output is also impressively designed and absolutely worth listening to.

Steve, as a multi-instrumentalist, keeps a low profile on this album for the most part and stays in his role as a guitarist – besides a harmonica part – which he fills completely. His second big job is the singing, which he takes on alone and does very well with it. Steve sings great over long stretches and doesn’t show weaknesses. Some might miss the vocals of Pete Hicks, who was active on Hackett’s earlier albums, but he is replaced by Steve himself in a fitting way. Nick Magnus is also back as keyboardist, as always in top form. In addition, Steve also has some classical instruments at the start with Chris Lawrence on double bass and Nigel Warren-Green on cello, but they are rather inconspicuous in the guitar-keyboard vault. Ian Mosley also sits on the drums for the first time, who would later – after the instrumental album Bay Of Kings – return for the sessions on the 1984 album Till We Have Faces, before finally turning to the British progressive rock band Marillion. This cast harmonises very well with each other and at many a point the harmony makes you sit up and take notice, especially the keyboards and guitars play on the same wavelength.

Essentially, Hackett’s sophisticated playing technique has not changed. He still produces ingenious melodies (in his role as composer) and realises them splendidly as usual. Thus, even though the album is not based on a clearly recognisable concept, he takes us on a journey through different sound worlds and moods, not least created by Steve’s (sometimes even almost experimental) guitar sound. Overall, the album sounds a bit naïve in places, but on closer listening it contains a certain maturity, sovereignty and experience that Steve has gathered from his previous albums. The small stylistic change, for example the no longer so numerous acoustic passages, also shows that Steve is open to new things and does not stick to a uniform style… whereby he still shows an existing continuity.

So we have nine songs, with a running time of a little less than 40 minutes. Maybe relatively short for a Genesis album, but it’s the content that counts:

Camino Royale

The opener shows where the album is heading and really gets going. The whole thing is introduced by a short but effective piano intro, before drums, guitars and an organ sound start. The main theme begins, a guitar theme underpinned by keyboards, which is taken up again and again in the course of the album. In fact, this theme has a special effect especially at the beginning of the album and virtually gives the starting signal for a mature record. After this introduction, the song continues in a structured way with the first verse, which in itself sounds very mystical and somehow wicked due to the echoing effect added to Steve’s voice. The vocals harmonise well with the keys in particular, which carry a certain mysticism despite their simplicity. Fittingly, the lyrics are also enigmatic, the meaning of which remains rather hidden. The chorus, on the other hand, is almost solemn and emotional, which is mainly due to the instrumentation, but also to the verse “Only the fool learns to get through”. Steve sings passionately and with joy and you notice that the band obviously enjoys the song as well. But it is this contrast between verse and chorus that works well.

Towards the end, the guitar theme is repeated once more before the song comes to a riffed conclusion. All in all, a powerful, punchy and dynamic song, outstanding as an opener and still popular today, especially because of its cult. By the way, the song was also performed very strongly live, to be seen, for example, in the DVD Somewhere in South America … Live in Buenos Aires.

Cell 151

The next track, which incidentally served as the opener in the American version of the CD, is almost unparalleled in genius. It starts with a steady, catchy rhythm, given by a deep string sound and with hard but regular drums. But an interesting guitar theme quickly inserts itself into this sound structure, then Steve begins with the lyrics. The verses sound very cheerful, the chorus on the other hand is performed in a highly emotional way and is melodically very strong. All in all a bit mysterious, the lyrics here are implemented in the sense of a story: Thematically it is about the inmate of a prison who is there because he shot his wife, whereby the song sounds ironic in itself, but still has a tendency towards seriousness. This inmate, who is saddened by his own past, lives in cell 151, but wants to leave as soon as possible because he feels he has left time behind.

But the piece also has a lot to offer in purely musical terms, because the text part is followed by an extended instrumental part that builds on the initial rhythm. Here, guitar and keys alternate in sections, with both repeatedly giving different melodies to the good, all of which fit strikingly into the overall concept of the song. The guitar inserts are particularly successful, as Steve inserts colourful effects, which gives the impression that the song serves as a playground for guitar effects. However, this is by no means a bad thing, but proves the playfulness of the song. It is conceivable that these musical sections represent the different ideas of the prisoner to break out.

All in all, this final part actually reminds a little of the title track of the Genesis album Abacab, since here, too, guitar and keys harmonise with each other on a rhythm (sounding almost improvised). Finally, Hackett brings the whole thing to a relatively quick fade-out after six and a half minutes, after the opening theme and the leitmotif of the opener are repeated once more: Whether the criminal has finally escaped, however, is up to everyone.

Always Somewhere Else

This song is instrumental and sounds uncomfortable and downright depressing at first. Calm piano playing and an aggressive, but dynamic electric guitar are in the foreground and convey a rather negative mood. All the better comes the unexpected, sudden turnaround, which has an immediate relieving effect. A very positive atmosphere is underpinned by fireworks of high keyboard tones, bass, which is particularly effective here, and the usual brilliant guitar work. The track is expressive and the contrast is technically brilliantly realised. The small masterpiece ends after four minutes with interwoven sounds of the keys, which Steve on the guitar again complements in the best possible way.

Walking Through Walls

This song is strikingly keyboard-oriented at first and begins with a simple, monotonous drum rhythm that runs through the whole song. Steve is quite sparing with the guitar in comparison, because only towards the middle of the song he contributes some “nasty” electric chords. His vocals are mighty aggressive, but sound a bit as if the meaning of the lyrics was not definitely clear to him. But the lyrics also don’t sound as if they have put emphasis on a central theme, but are simply meant to sound good, so that the voice can practically be regarded as another instrument. Somehow, the whole thing sounds a bit like the typical 80s style, or at least Steve’s interpretation of it, which is not at all disturbing. So the song is largely simpler, in sound and also in structure, than the predecessors on the album.

Nevertheless, Steve comes up with a guitar solo after the third verse, as a little finale, so to speak. Fits well, but would be out of place and disturbing in many other Hackett songs. There’s something to get your attention in the final part, where Steve repeatedly sings us a never-ending “Walking Through Walls”: each verse is underlaid with weird sound effects, with “blopping” and chewing noises. Sounds interesting, but what that means for the song is open to debate.

All in all, rather an average number. But especially here the stylistic change becomes clear, because Hackett didn’t do anything like this in the 70s.

Give It Away

Here Steve offers a really very emotional and strong track! The drums are again multifaceted, the song is very lively. The verse is dramatic and creates tension before it leads perfectly into the chorus, which itself has a great melody. The correspondence between guitar and vocals is also clearly successful, somehow you notice here that the lead guitarist also takes over the job of the singer. Steve delivers the lyrics very convincingly: It’s about the first love, which you mourn after when you lose it. But before you lose yourself, you should change direction and “give away” this love until one day you realise that you are over it.

The calm middle section is also superbly realised, in which the opening motif is rung in again acoustically. Finally, the drums start again and a fantastic guitar solo brings the song to a close.

Weightless

Exuberant mood, loose piano that sets the tempo and a relaxing tempo throughout mark this piece. The song is literally what it’s called and makes an almost weightless impression. A very light thing, in which Steve, as he says himself, puts his experiences of hang-gliding over Rio de Janeiro. The lyrics describe this topic unambiguously and the feather-light realisation of the song supports the lyrics. Nevertheless, the instrumentation is not kept too minimal and ultimately brings the necessary power. Just like the experience of floating weightlessly between clouds and beaches.

But some may ask themselves how seriously the song can be taken. In purely musical terms, it is certainly not a challenge for the opener, for example, but it fits on the album and at this point, as something uncomplicated.

Group Therapy

Already the title of this admirable instrumental is grotesque. This impression is confirmed in the course of the song. It is actually a typical Hackett instrumental, an anthem that has been heard before in a similar vein, for example on Ace Of Wands from Steve’s first album, Voyage Of The Acolyte, but never gets boring. On the whole, the song offers versatility and works through the different parts, which artistically skillfully merge into each other. All parts seem very dynamic, whereby the song is progressive from the start: many tempo changes and a perfected interplay of all actors make it unique and lively.

A particularly remarkable idea is the section with the question-and-answer game of electric guitars. Several guitars take turns and sound like the participants in the therapy, in which everyone throws something into the round, sometimes faster, sometimes slower, sometimes louder, sometimes quieter. This song idea deserves respect and as suddenly as the aria started, as abruptly it ends. The hectic song is fun!

India Rubber Man

This ballad starts quietly, which is a rarity on the otherwise loud Highly Strung, and maintains a very nice atmosphere until the end. Through the emotive delivery, the song sounds almost tragic, dealing with the rubber man who is always travelling and probably doesn’t quite know how far he can go himself. Strings and piano play beautifully with each other and give the song a pleasant atmosphere, which comes into its own especially in the outro. The harmonica solo in the middle of the song is also worth listening to and sounds like it was played on a meadow after a hot summer day at sunset. Here, an electric guitar melody from Always Somewhere Else is used and skilfully implemented in quiet, relaxing tones. Conceptually, this reference fits, as the India Rubber Man is literally “always somewhere else”. The song has class and soothes again before it transitions into the finale!

Hackett To Pieces

After a deep sound, it starts again with the opening melody of the opener! The transition to this piece is perfect and has the character of an arc of tension. Dynamics and aggressiveness are the hallmarks of this song, although the guitar itself only kicks in later. The leitmotif is repeated slightly changed before the piece fades out with bombastic drums and a deep string sound throughout. It rounds off the album flawlessly, precisely because it makes reference to the first song. The album could not have ended better.

Taken together, this is an absolutely convincing work, which for the most part sounds mature and is on a high level. As with other Hackett albums, the guitar playing is extraordinarily strong, forming a great team of two, especially with the keys, and convincing on many occasions. Probably not all Hackett fans will like it, as it differs quite a bit from Steve’s albums from the 70s, but it has an impenetrable character that makes an impact.

Ultimately, this is a successful record and the production is also well done. Steve simply has this rocking sound and shows it with passionate commitment, which results in this wonderful record. Hats off.

Highly Strung was first released on 22 April 1983.

Author: Ole Uhtenwoldt (2014)