- Article

- Read in 12 minutes

Steve & John Hackett – Sketches Of Satie – album review

In 2000, Steve and John Hackett released an album with music from Erik Satie, a french composer from the early 20th Century. Bernd Vormwald wrote the review back in 2000.

(originally published on our German website in 2000, now available for the first time in English)

Steve Hackett notes this in the booklet for Sketches of Satie: „John an I had long talked about a project involving Satie’s music. Would it require an orchestra or could we use the full tinal range of our own two favoured instruments to create a sound canvas worthy of the keyboard-based writing? Either way it would be retrun to our musical roots when we first became aware of ‚Atmospheric‘ music (…). There always was a love of music in the family home but not specifically the ‚Classical‘ tradition – I’d say we found our way to this music ourselves without being pushed. For us, Satie was definitelly a man ahead of his time. Unlikely modulations abound and the Minimalists were taken from him as would Jazz. (…) Transposing from piano comes with its own problems … we felt the original keys were perfect for flute but lay outside the range of guitar … detuning my strings to encompass piano range, I moved my 6th string as much as a whole octave lower than usual to give the often complicated harmonies the fullness of support they needed. By way of special thanks, the project would not have been possible without Sally Goodworth’s original tempo map combined with Roger King’s unbelievable patience and concentration during the recording process. (…) I can’t fully describe my delight and joy that the sessions went so well and that the album, long overdue, is now complete. I may be sticking my neck out here but don’t believe John has ever sounded in finer form, he was obviously born to play Satie – as I am sure you’ll agree. I hope that you’ll be equally captivated, as we were in those early years, by the beauty of one of France’s most original composers.“

Steve Hackett and Erik Satie? Yes, that works! Both Satie and Hackett are truly progressive musicians in the sense that they progress, develop, innovate, experiment and rebel against traditional forms. Satie wrote pieces that can be described as idiosyncratic, unusual, bizarre, revolutionary, in a word: progressive. If you have followed Steve Hackett’s output from the 1970s to this day you will also find enough examples for that kind of music; tracks such as Slogans, Myopia and Omega Metallicus, for example have never grown famous or commercially successful because they are so weird. Only Satie’s Gymnopédie No.1 is known to a wider audience, while the rest of his rich oeuvre is left for specialists. This is probably also going to be the fate of the album Sketches Of Satie that Steve Hackett recorded with his brother John in 1999 and released in May 2000: Lovers of classical music will probably not notice while Hackett fans are perhaps more into albums like Darktown. However that may be, the delicious adaptations of Satie’s piano pieces for guitar and flute have made Sketches Of Satie an extraordinary and wonderful album of sometimes brittle beauty that deserves a much larger audience. The album will be first time you listen to it will be exhausting, but if you give it more than one go you will discover a wonderful world of music. Luckily, the CD also has excellent sound quality. The virtuoso Hackett brothers lives up to all other Satie recordings. In Steve Hackett’s album catalogue Sketches Of Satie is lumped together with Bay Of Kings, Momentum and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and we should not forget that Steve was the solo artist in a performance of Vivaldi’s Concert for Guitar by the London Chamber Orchestra at the South Bank Centre in 1997..

The only thing worth criticizing about the album is the illogical order of tracks (after all, Willow Farm does not go before Lover’s Leapeither), but in these enlightened days of playlists this only flaw of the Sketches Of Satie is quickly resolved. The chronological order of tracks (except for Gnossiennes No.5 and No.6) for this review is 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 13, 14, 15, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Trois Gymnopédies (1888)

No. 1: Lent et douloureux

No. 2: Lent et triste

No. 3: Lent et grave

In the liner notes for Gymnopédie No.1 in Sketches Of Satie Steve Hackett says: „It must have taken me a good ten years to find out who had written a haunting melody I kept humming to anyone who was vaguely musical and when I finally did find out, no-one, not even the French, could tell me what a ‚Gymnopèdie‘ was … I doscovered in time that it referred to a frieze of dancers on a Grecian urn … well known to academics perhaps, but to discover it for oneself was all the more powerful.“ Similarities between Steve Hackett’s classic Kim and all three Gymnopédies are obvious, and you could say that Hackett added a fourth Gymnopédies to Satie’s three with Kim.!

The French term „lent“, or “lento” in our musical language, means “slow and drawn out”. The additions of “douloureux”, “triste” and “grave” must be attributed to Satie’s satirical vein: All those three words mean more or less the same thing, so they lure the pianist (or the players of guitar and flute in this case) into the same interpretation – who can differentiate between a “painful”, a “sad” and a “heavy” sound? These three gentle and fragile, dreamy, warm-hearted Gymnopédies indicate that, despite his catty behavior, Satie was a sensitive man who desired harmony – and you would not guess that from his sharp-tongued commentaries. Satie’s “hit” Gymnopédie No.1 is quite well-known in Germany because an insurance company uses it as the background music for their advertisements. And Gymnopédie No.2 is by no means as sad as the title comment “triste” would suggest (unlike Gymnopédie No.3)

In their liner notes to the CD The Best Of Erik Satie (Naxos 8.556688), Keith Anderson and Tilo Kittel explain: “The peculiar title,Gymnopédies, refers to ceremonial cult dances of naked boys in ancient Greece (gymnos = nude, paidos = boy). The steady rhythm in the manner of a slow waltz fills the three pieces with wistful nostalgia and plain solemnity.” – Well said, you friends of classical music, and little can we add to that except for the fact that there are orchestral versions of the Gymnopédies by Claude Debussy and one Monsieur Roland-Manuel that were used by Woody Allen in his 1988 film Another Woman.

Gnossiennes (1890 – 1897)

No. 1: Lent (1890)

No. 2: Avec Étonnement (1890)

No. 3: Lent (1890)

No. 4: Lent (1891)

No. 5: Modéré (1889)

No. 6: Avec Conviction Et Une Tristesse Rigoureuse (1897)

Let’s hear Anderson and Kittel again (and expanded): “The explanation for the title, Gnossiennes, remains ambiguous. ‘Gnosus’ [sic!] is the ancient name of Crete while ‘gnosis’ means ‘insight’ or ‘judgement’. The Gnossiennes recall the mysterious, ancient world of Minoic culture on the Greek island of Crete and the important palace of Knossos (built around 1900 BC., the location of the legend of Theseus and Ariadne) and the labyrinth of Daidalos.” These six pieces with their various moods from depondent melancholy to elation and happiness have one thing in common: Except for No.4, they all have a slight touch of sirtaki, so we prefer the explanation based on ‘Gnosus’. Says Kittel: “The musical relationship ofGnossiennes 1-3 to theGymnopédies is almost palpable.Gnossiennes 4-6 are different in that their harmonics are more complex and the way they have to be played is more complex. The tonality of major and minor keys is replaced with oriental Greek, modal harmonics. It is striking that theses tracks are divided into building blocks, as it were: The little phrases from which the compositions are constructed, can apparently be replaced or repeated as often as you like.” The Gnossienne notes do not have any bar lines, and Satie’s peculiar directions for performance reappear:

Gnossienne No.1: „du bout de la pensée“ = „the tip of thought“ / „postulez en vous-même“ = „consider this in your heart“ / „sur la langue“ = „on the tongue“

Gnossienne No. 2: starting with „avec étonnement“ = „with astonishment“ / am Ende „sans orgueil“ = „without pride“

Gnossienne No. 3: „conseillez-vous soigneusement“ = „consider carefully“ / „ouvrez la tête“ = „open your mind“

Gnossiennes No. 4-6: no instructions

Attributing any deeper meaning to these instructions beyond a frown and a smile would probably only have brought a grin to Erik Satie’s face …

Pieces Froides (1893)

Airs À Faire Fuir I

Airs À Faire Fuir II

Danses De Travers II

A bittersweet atmosphere pervades the playfully dancing Airs À Faire Fuir I. Airs À Faire Fuir II sounds more sedate and positive than Airs À Faire Fuir I. Peculiar chances between major and minor keys are the main characteristic of Danses De Travers II, which Steve Hackett plays on his own.

Avant-Dernières Pensées (1915)

1. Idylle À Debussy

2. Aubade À Paul Dukas

3. Meditation À Albert Roussel

These three “penultimate thoughts” were written without bar lines. Satie added some of his peculiar comments:

1. Idylle à Debussy

„Que vois-je? Le Ruisseau est tout mouillé et les bois sont inflammables et secs comme des triques mais mon coeur est tout petit.“ – “What do I see? The stream is all wet and the woods are flammable and dry as a stick but my heart is very small.”

2. Aubade À Paul Dukas

„Ne dormes pas, Belle Endormie, ecoutez la voix de votre bien-aimé, il pince un rigaudon.“ – “Do not sleep, Sleeping Beauty, hear your sweetheart’s voice, he plucks a rigadoon.”

3. Meditation À Albert Roussel

„Le poète est enfermé dans sa vieille tour, voici le vent, le poète médite, sans en avoir l’air, tout a coup, il a la chair de poule, pourqoui?“ “The poet is locked in his old tower, here is the wind, the poet meditates without looking like it, suddenly he has goosebumps, why?” The piece ends when the poet get an upset stomach from “mauvais vers blancs et désillusions amères, “bad blank verses and bitter disappointments.” (Come again?)

A gigantic verbal wind blows across these three small, fine, peculiar and interesting tracks. Steve Hackett accompanies himself without any flute music by his brother. In a live situation he’d need a second guitarist

Nocturnes (1919)

No. 1 (Dedicated to Marcelle Meyer)

No. 2

No. 3 (Dedicated to Valentine Gross)

No. 4

No. 5

Says Kittel: „These pieces are from Satie’s late period when he tried to create situation music that is completely contrary to bourgeois expressive music. Satie called it musique d’ameublement: The listener ought not to pay more attention to the music than to the furniture. Before his music was performed he asked the audience to behave as if no music was being played – at Satie’s time that was revolutionary.”

Satie was a revolutionary indeed, a visionary who makes his way far away from the established routes. In order to understand Satie’s thinking and behavior one has to become familiar with his life and the time in which he lived.

Frédéric Castello writes about the Nocturnes: “By this time, Satie has developed a composing style he calls dépouillement, skinning. Everything he considers superfluous is cut away and yet the character of a ‘nighttime piece’ remains – which proves that you do not need a huge arsenal of instruments to create big effects.”

The beauty and the magic of these sophisticated and weird nocturnes reveal themselves only by and by to the listener. Satie had originally planned to write six of these most interesting nocturnes. Once you are familiar with them you will not want to let them go.

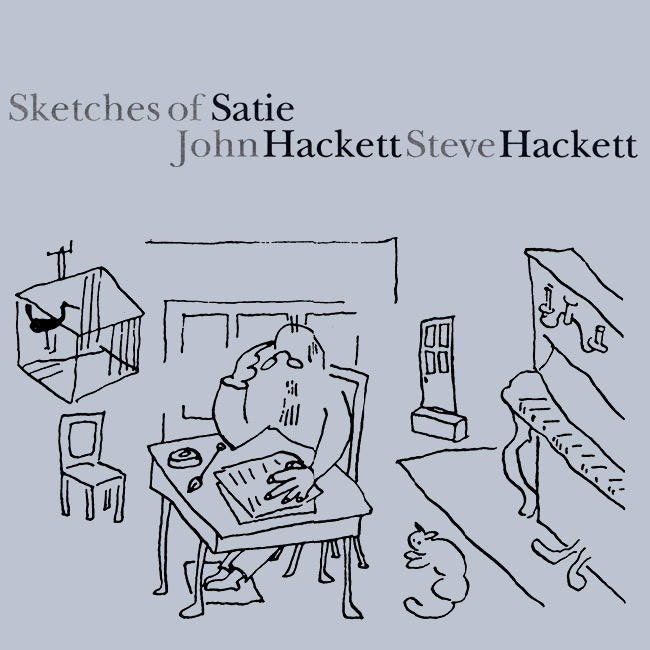

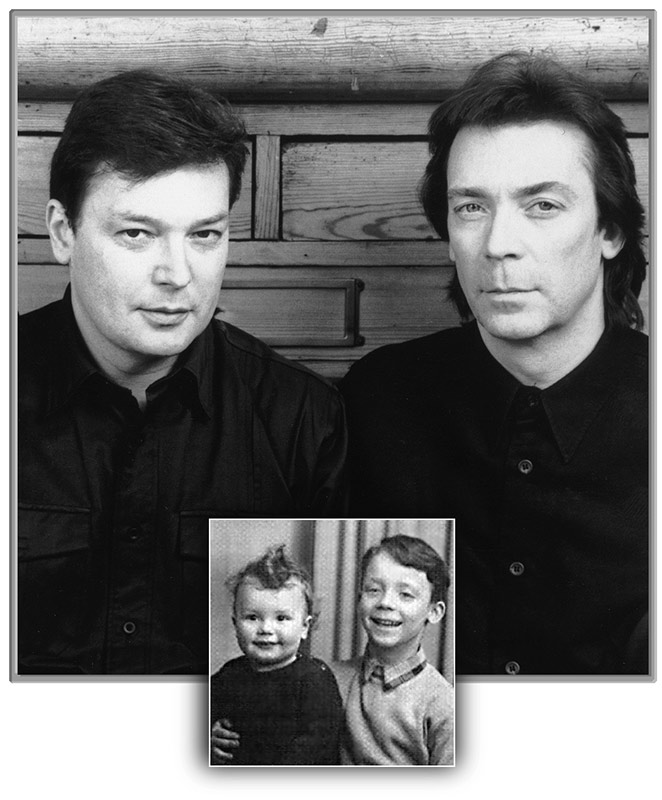

Though Kim Poor sketched Steve and John on the rear, the drawing of Erik Satie on the front cover was done by an unknown artist. The rear of the booklet brings back wistful memories of the Duke cover times. Times were good. The photo of John and Steve in the booklet was taken on April 24, 1956, and the boys haven’t changed a bit…

And another fan request…

Hello, Steve and John! Please venture out again together into these musical seas, be it with cover versions or your own material – never mind: This kind of album may perhaps attract only a handful of listeners, but those happy few will find wonderful and dear companions in those albums on their ways as music aficionados.

Tracklist:

1. Gnossienne No. 3 (2:24)

2. Gnossienne No. 2 (1:55)

3. Gnossienne No. 1(3:17)

4. Gymnopédie No. 3 (2:36)

5. Gymnopédie No. 2(2:52)

6. Gymnopédie No. 1 (3:54)

7. Pièces Froides No. 1 – Airs à faire fuir I (2:46)

8. Pièces Froides No. 1 – Airs à faire fuir II (1:36)

9. Pièces Froides No. 2 – Danse de travers(2:05)

10. Avant Dernières Pensées – Idylle à Debussy (0:56)

11. Avant Dernières Pensées – Aubade à Paul Dukas (1:10)

12. Avant Dernières Pensées – Méditation à Albert Roussel (0:54)

13. Gnossienne No. 4 (2:41)

14. Gnossienne No. 5 (3:19)

15. Gnossienne No. 6 (1:41)

16. Nocturnes No. 1 (3:30)

17. Nocturnes No. 2 (2:14)

18. Nocturnes No. 3 (3:36)

19. Nocturnes No. 4 (2:49)

20. Nocturnes No. 5 (2:26)

total: 49:02

Sketches Of Satie was released in 2000 and is available on amazonUK and iTunes.

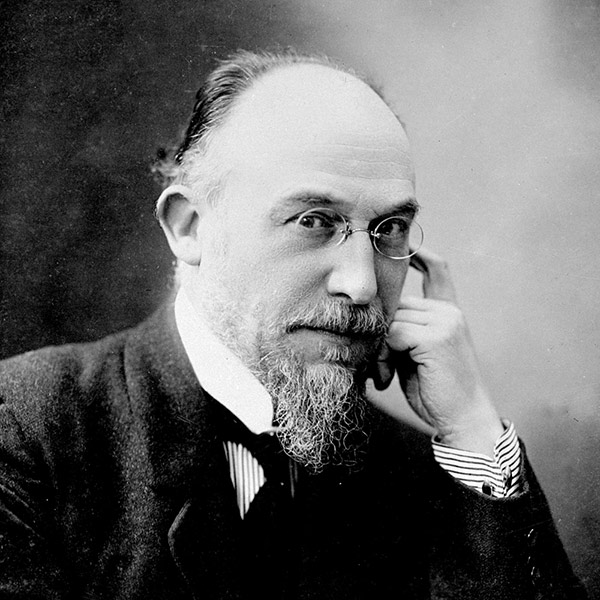

Erik Satie was born in Honfleur / Calvados, Normandy, on May 17, 1866. His father dealt with boats (and went on to become a publisher). The only thing known about his mother is that she was from Scotland. The Satie’s family moved to Paris, but after the death of his mother in 1872 Erik went back to Honfleur to live with his grandparents for six years until 1878. He read music at the Paris conservatory until he was expelled because he lacked industriousness. In 1888 his father encouraged him to write the famous Gymnopédies. For a couple of years Satie earned his living by playing in cafés and writing music for the cabaret. He was a regular at Le Chat Noir bar where artists and intellectuals would spend their time. It was there that he met Claude Debussy and won his friendship. In 1898 Satie moved to the Paris suburb of Arcueill where he would stay until his end. From 1905 to 1908 he studied again, at the Schola Cantorum this time, and got his diploma. From 1911 onwards Erik Satie was recognized and appreciated more, not least because of the support he received from other composers such as Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel (the one with the Bolero). A group of like-minded artists flocked around Satie at about 1918; they supported new musical ideals and came to be called Les Six or Les Nouveaux Jeunes from 1920. Owing to an immoderate consumption of alcohol Satie’s health began to decline from 1923 until he died in 1925 from a cirrhosis.

A German music encyclopedia, Neues Großes Musiklexikon, writes: “The rebellion against conventional schemes of musical academism that got him expelled from the Conservatoire is to a certain degree the uniting element in Satie’s oeuvre: a) extreme liberties in the notation as a dominant characteristic in his music, b) strange, peculiar titles and bizarre “vexations” (performance instructions) such as “light as an egg” or “here comes the lantern”. When Debussy asked him to “Mind the form of your compositions” Satie reacted by writing Trois Morceaux En Forme D’Une Poire (“Three Bites In The Form Of A Pear”), c) a new form of writing down music (with remarkable graphic clarity and technical perfection) in red ink and without bar lines.

The same music encyclopedia adds that Satie’s work as a musical precursor showed in stacked fourth chords and undissolved sevenths and ninths, and notes that this influences Debussy, Ravel and others.

Another encyclopedia called Die Musik (The Music) reports that Satie, who lived in rather poor circumstances, was considered an eccentric, peculiar loner and musical joker. His strange sense of humour showed in the fact that he founded the Église Métropolitaine d’Art De Jesus Conducteur, a kind of church with an incredible large number of parishioners: Satie was its only member.

Satie’s wry sense of humour also shows in his piece Vexations. It consists of 180 notes, which is nothing special. What made it special is the instruction that the piece was to be repeated 840 times. Ten pianists took up that challenge in New York in 1963. They played for eighteen hours …

When the comments he added to his pieces drew more attention than the music itself, Satie apparently lost his humour and forbade his instructions to be recited during the performance.

By Bernd Vormwald

English by Martin Klinkhardt

Main sources (in German): Neues Großes Musiklexikon (Weltbild Verlag 1990), Die Musik (Christian Verlag 1979)