- Article

- Read in 8 minutes

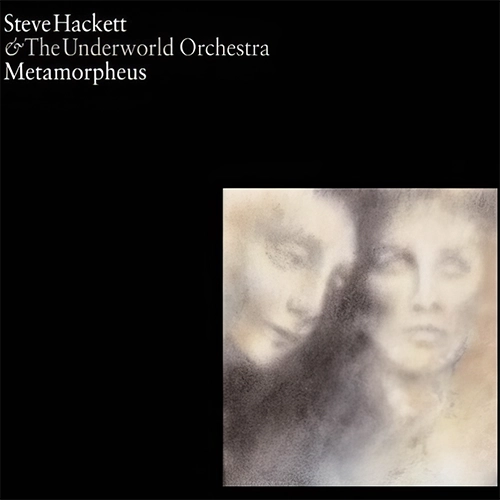

Steve Hackett – Metamorpheus – review

After the artistic and commercial success of Steve Hackett’s version of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream as a guitar concert in 1997 another project like that was to be expected. And indeed it was announced a couple of years ago and published eight years after its predecessor.

After the artistic and commercial success of Steve Hackett had with his musical rendition of William Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream (1997) another project in that vein was to be expected. Indeed it was announced a couple of years ago. Eight years after its predecessor the new project was finally released.

Once more Steve picked a theme that had inspired many a composer before him. The Greek myth of Orpheus had been the sujet of several operas such as Orfeo by Claudio Monteverdi, which is considered the very first opera, Orpheus And Eurydice (by Christoph Willibald Gluck) or Jacques Offenbach’s Orpheus In The Underworld.

You can read up on the Orpheus myth in any good anthology of classical myths – or check out the Metamorphoses by classical Roman poet Ovid. It is a collection of stories in which people turn into other creatures or things. Metamorpheus is a combination of the two words “metamorphosis” and “Orpheus”, and by no means a new pun. (The album title has probably nothing to do with Morpheus, the Roman god of dreams, who makes an appearance in Genesis’ Scenes From A Night’s Dream.)

Steve uses other or additional sources than the ones mentioned above or his own fantasy. His version of the story contains a number of additions and changes compared to the original. All fifteen parts of the concerto are described in a couple of lines in the booklet, and we are going to tell the story the way Steve does it.

The story begins with three rings of a bell (complete with echoes) in D. D major is the key in which most of the music is written. It is the basic key of the first dissonant guitar chord, an arpeggio consisting of a minor seventh, a minor ninth and an enlarged eleventh, i.e. an enharmonic change like a D7 chord with an added chord in As major. It is followed by one of the main themes of the opus, perhaps to be called “Orpheus’ theme”. Because of an enlarged second it seems like an oriental scale. Guitars and string instruments take turns or complete each other. They use bits from the main theme and the eleventh chord to represent The Pool Of Memory And The Pool Of Forgetfulness. Orpheus, son of Kalliope (the muse of poetry and songs) and the King of Thracia (and son-in-spirit of Apollon) looks into that first lake to recognize his strong links with nature. But it is from the other water that he drinks so that he can make his way on earth.

Orpheus’ birth follows without a break, he comes To Earth Like Rain. This merry song is lead by the guitar, while the strings stress the wavy pulse of the main theme.

Orpheus links to nature and his vocal talent soon become apparent. When he sings, he joins man and beast and inanimate world in harmony. This is expressed in the quasi-choral Song To Nature. The chorus is presented by strings and guitar. A guitar improvisation provides the link to the next piece which begins attacca:

Orpheus meets Eurydice, most beautiful of the Naiads (female minor deities of springs and brooks). She is the woman of his dreams, the One Real Flower. This virtuoso guitar solo reaches us in a glorious allegro – Metamorpheus is dedicated to Steve’s wife Kim Poor, by the way.

The string group is augmented with just a little bit of guitar-playing when it plays the A major waltz for the dance of the Muses who celebrate the wedding of Orpheus and Eurydice on The Dancing Ground. In this piece it becomes evident again (as in parts of the Midsummer Night’s Dream) that Steve and his co-workers Roger King and Jerry Peal are not very accomplished at arranging music for orchestra. If you compare this dance to waltzes from Tchaikovskiy’s ballets it comes across somewhat stilted. The dance takes an unexpected turn when Eurydice suddenly has a premonition. This is expressed musically as a series of threatening chords that are repeated alarmingly often, grow more and more dissonant and peak in a horn’s call. The piece ends in a dissonant string chord which is followed by the first break on the CD.

The next piece has to be considered as a central item of Metamorpheus because of its length and number of different themes. It is not really necessary for the development of the story: When the couple embraces,That Vast Life passes before the listeners ears. Many new themes are introduced, bits where only the guitar can be heard are mixed with orchestral parts. There are a number of modulations from D major to A flat and C major. Some of the previous themes are quoted, e.g. a piece from the guitar improvisation at the end of Song To Nature (from 8:03, or at 2:50 in STN) and a theme from the waltz The Dancing Ground from 10:59 (or at 0:42 on TDG).

Eurydice Taken by death – the naiad’s premonition comes true: In Steve’s version she is chased by the famous mythical hunter Aristaios in her wedding night. Far away from Orpheus, she dies from a snakebite. We hear initial dissonant chords followed by ascending and descending dominant seventh chords – all on solo guitar – that lead into a new theme, perhaps one of sorrow. The strings come in again and quote Orpheus’ theme.

The next piece, Charon’s Call, begins without a break, and one has to wonder why divisions between the tracks were placed so carelessly – or why they were made indeed. Orpheus embarks on his journey to the netherworld to follow Eurydice. On his way, he has to cross a river. Charon the ferryman conveys him to the other side (incidentally, an image of Charon can be seen on the cover of Tony Banks’ album A Curious Feeling). A single violin continues the theme of the previous piece and the mourning melody. A transition on the oriental scale prepares the listener for the orchestra that repeats the mourning theme before the piece ends in arpeggi on the guitar.

We do not only approach the netherworld proper, but also two very accomplished pieces of this opus:

At first, Orpheus encounters the three-headed dog of hell, Cerberus, who guards the entrance to the netherworld. Enchanted by Orpheus’ soothing song the dreadful Cerberus remains At Peace. The music builds a majestic entry to the netherworld by brass fanfares, a snaredrum and glissandi. A latent threat that does not erupt is quietly insinuated by bass figures that resemble Tigermoth or Clocks.

Under The World – Orpheus Looks Back. That is the title of the chapter in which Orpheus enters the netherworld and protests his love for Eurydice to the underworld’s royal couple of Hades and Persephone. He moves all the shadows and the rulers of that place so much that Eurydice is permitted to come back with him. A first. There is only one condition he has to meet. When they travel back to the upper world Eurydice has to walk behind Orpheus, but he must not turn to look at her before both have left the underworld. Tragedy ensues: Just before they reach the gates of the netherworld Orpheus is overcome by anxiety because he cannot hear his wife’s steps behind him and by his longing for her. He turns to look at her only to see Eurydice sucked back below for good. The piece begins with a rhythm of snare drum and bass which resembles Maurice Ravel’s famous Bolero. The strings add ethereal descending chords that sound very much like the intro to Can’t Let Go. A gong sounds and Orpheus’ theme is repeated in an oriental-no-longer variation. Ravel-like bits re-occur, the music grows louder, it is striding upwards, as it were, and increasingly happy when suddenly a series of loud and tense chords represent Orpheus’ anxiety and the looming harm. A sudden descending glissando illustrates Eurydice sliding back into the netherworld.

Orpheus’ heart breaks. He is denied access to the underworld. His magic art fades away and he begins to despise all worldly love. The Broken Lyre is a symbol for this. It is an elegiac piece for solo guitar – the strings come in only near the end.

More evil appears under the heading of Severance. A horde of Bacchants, i.e. women followers of the god Dionysos, appear to punish him because he rejects all female love. They stone him to death and tear him apart. The river Hebros carries his head and his lyre. The orchestra has a very tragic sound when it quotes the mourning theme. Bass pieces like the bass pedal sound from Spectral Mornings that already appeared in the Cerberus piece make for an extremely threatening sound. Fast and high notes represent the things hurled at Orpheus.

The ensuing Elegy is introduced by the flute which plays an important role throughout the piece. It is a pity that the motif from 0:14 to 0:20 is not picked up upon. Once more, there are ringing bells. Orpheus’ body is interred at the foot of Mount Olympus. The birds above his grave sing more beautiful than anywhere else.

Orpheus’ head and his lyre are carried to the island of Lesbos, while his spirit journeys into the underworld to be united with Eurydice for ever. Steve, who believes in reincarnation, calls it the Return To The Realm Of Eternal Renewal. It is introduced by the dissonant arpeggi from the first piece. From 1:51, we once more hear the theme of Orpheus meeting Eurydice for the first time.

The Lyra is offered to a temple of Apollon. In the end it is hung up on the sky where it turns into the constellation of the Lyre. For this finale, Steve devised a particularly solemn theme. He even quotes some familiar motifs: A piece of The Fountain Of Salmacis as released on Genesis Revisited (from 0:31 onwards), then some tunes from the big embrace (1:40, actually it is a melody from the Dancing Ground, 1:58, 5:04 and 6:06 onwards). Then there also is a sweetened variation on the mourning melody (5:49 onwards) which probably represents the sorrow overcome.

The music is kept quite simple, though one would wish for more innovation and intensity from Steve. A professional arranger like Simon Hale (who arranged Seven for Tony Banks) would have been a good step, though the three arrangers did not do a bad job at all. The production was obviously meant to be not as big as for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. There are fewer instruments in the orchestra (strings, flutes, trumpet and horns) and it is a not so well-known ensemble. Steve probably also wanted to steer clear of a label such as EMI.

Still, there is no reason for a Hackett fan to bypass this record. You get many of the advantages of a Hackett release, such as large-scale melodies spanning major parts of a recording, a differentiated mix of the music and the trademark acoustic guitar. There is, however, no big hit on this record like Celebration on the Shakespeare project.

The booklet is graced by diaphanistic oeuvres by Kim Poor. It contains textual notes to all fifteen pieces, the credits, a well-known photo of Steve and a selection of quotations from Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets To Orpheus (in English, of course).

Should Hackett go for another project like this, it would need more creativity and something innovative. Touching as the Orpheus myth may be, one should seriously consider whether a musical rendition of it can dispense with vocal efforts (after all, that is Orpheus’ trademark) and why the expression “metamorphosis” should occur in the title when there is little of it in the music.

by Andreas Lauer

translated by Martin Klinkhardt