Even with two solo albums released it was still unclear which way Peter Gabriel’s solo career would develop. While the solo debut had been hailed as Gabriel’s much-desired return to music, the gloomy and hit-less second album seemed to have stopped that development. Lots of live performances kept his profile high – not least the legendary performance at the Essen Rockpalast in 1978. When Gabriel installed his own private studio in an old mansion near Bath it seemed to trigger a whole new burst of creativity. Without the need to pay attention to studio fees he was free to try out new ways of producing music.

The new album would certainly sound as if there had been many experiments with various effects. Peter Gabriel also continued his habit of testing new material live. A number of festival performances offered a good opportunity. A rough percussive version of I Don’t Remember, one of the central tracks on the upcoming album, was a piece Gabriel had been touring with since 1978. As important as the own studio was the choice of producer. It was Steve Lillywhite, the new star of the UK studio scene (known for his work with Ultravox, XTC and later U2), who sat down at the mixing-desk. He is considered a follower of Brian Eno’s, who, in turn, had provided some effects for Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway.

The songs for the new album were based on rhythms; melodies were secondary. One of the most important devices for this new way to write songs was rather unspectacular: it was a Paia drum machine that cost either 60 pounds or 60$, depending on which source you follow. Whatever the price, it certainly was no high-end product. Keyboarder Larry Fast had recommended the device and provided basic instructions on how to use it. “For a failed drummer like me it was a joy to be able to produce grooves that continued when I took my hands off the keyboard”, says Peter, who also praised the “almost maniacal qualities” of the drumbox.

The focus on rhythm led to another idea that decisively shaped the sound of the album and challenged the drummers who worked on that album: The idea was for the drummers not to use any cymbals at all. The drummers were Jerry Marotta, Gabriel’s “own” tour and studio drummer, and none other than Gabriel’s former band mate Phil Collins. Gabriel wanted the album to be “metal-free”, as it were, to achieve a more percussive drum sound and a more aggressive overall impression. This called for different solutions, so Collins simply mounted further drums to the place where the cymbals would have stood – simply to avoid hitting thin air when he would go for the cymbals from habit. Sound engineer Hugh Padgham and Collins also developed a new sound through a combination of noise gates, compressors and limiter effects. Strongly compressed drum sounds became all the more powerful before they were cut off before they fade away naturally, which made the drums sound even harder. These effect experiments are considered the genesis of the Phil Collins signature drum sound he would use on In The Air Tonight, No Son Of Mine and many other recordings so that it became his trademark sound.

Further effects and unusual sounds developed at leisure in Peter’s own studio were provided by a piece of equipment that was brand new at the time: the Fairlight sampler. After he was given a special presentation of this new piece of music technology Peter Gabriel was so enthusiastic about its possibilities that he began to work with the “Computer Musical Instrument” at one – and also took over the import and distribution of the device manufactured in Australia. The Fairlight provided not only the opportunity to sample your own sounds and create new ones from it but there were also a number of preset sounds to facilitate its use.

This album marks the beginning of Peter Gabriel’s working with guitarist David Rhodes, a collaboration that lasts to this day. Tony Levin, who worked with Gabriel from the beginning of his solo career, can only be heard on one song because he had other obligations. Other bass parts were played by John Giblin who would be heard on Phil Collins’ first two solo albums. Paul Weller (then of The Jam) was a spontaneous addition to the list of musicians on And Through The Wire. Weller worked in the studio next door at the Townhouse complex and played the rhythm guitar between recordings for his own album.

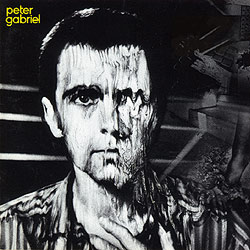

The cover showed a photo of Gabriel’s face seemingly dissolving and dripping down; hence the album’s nickname Melt. It was the first album on which Peter Gabriel integrated an increasing number of quotes from his new interest, world music, into his own songs. The African choir on Biko was still more of a quote than an appropriation, and there were only few elements from world music compared to the extensive use he would make of it on later records. The album shows how Gabriel set out to join world music and rock: There are those ubiquituous xylophone sounds, and the work on drums and other percussion – in rhythms as well as the instruments employed (e.g. the surdu on Biko). The extreme focus on rhythm also had an effect on the lyrics. Gabriel’s statement that the sound of the words in particular and the lyrics on the album in general were made to fit the rhythm rather than vice versa was surprising as it came from a musician who had been considered a kind of concept artist until then. With Melt, Peter Gabriel made a clear step towards becoming a political artist. Games Without Frontiers became his second big single hit after Solsbury Hill.

The cover showed a photo of Gabriel’s face seemingly dissolving and dripping down; hence the album’s nickname Melt. It was the first album on which Peter Gabriel integrated an increasing number of quotes from his new interest, world music, into his own songs. The African choir on Biko was still more of a quote than an appropriation, and there were only few elements from world music compared to the extensive use he would make of it on later records. The album shows how Gabriel set out to join world music and rock: There are those ubiquituous xylophone sounds, and the work on drums and other percussion – in rhythms as well as the instruments employed (e.g. the surdu on Biko). The extreme focus on rhythm also had an effect on the lyrics. Gabriel’s statement that the sound of the words in particular and the lyrics on the album in general were made to fit the rhythm rather than vice versa was surprising as it came from a musician who had been considered a kind of concept artist until then. With Melt, Peter Gabriel made a clear step towards becoming a political artist. Games Without Frontiers became his second big single hit after Solsbury Hill.

Intruder

The album kicks off with Phil Collins’ hard, monotonous and driving drum rhythm; a creepy atmosphere evokes the emotions of a burglar. Sinister shouts scare the listener before the intruder begins to speak with a breathy voice. The focus is on the act of burglary itself and the excitement the intruder feels in the silent encounter with their victim. An intense song that gets under your skin, but at the same time points at the new musical direction Gabriel takes with its focus on rhythm.

No Self-Control

A looped sample introduces the second song with Phil Collins who gives an even more impressive presentation of his new big drum sound. It is accompanied by elements of Minimal Music such as the maniacally driving xylophone. A restless, hunted man reveals his feelings, a nervous tension spreads, breaks out into a thunderstorm of sounds and desperate cries of “no self-control” before eventually returning to the nervous mood of the beginning. Feelings of guilt, of insecurity, repressed feelings – perhaps it is the Intruder who has to face his own dark side here? Its drama would make No Self-Control a live favourite of Gabriel’s next tours, the more so because live it became even more intense.

Start

A snippet of a song. With broad synthesizer sounds and jazzy saxophone this is more an intro to a song than a song in its own right. There are a number of fine ideas in these less than 90 seconds, but they don’t seem to fit too well to the song after, I Don’t Remember. It makes you wonder what other song is hiding in here.

I Don’t Remember

Another monotonous rhythm on drums and bass with ever-repeating guitar fills and a melody that seems almost too dull in the chorus. The lyrics are about amnesia, inability to communicate, withdrawal into one-self and the loss of the own identity in the masses. The structure is very simple, verse-chorus-verse-chorus-chorus. In the beginning and at the end the band toy with some sounds, then there is Gabriel’s distorted voice and a technological soundscape of distorted guitars, synthesizer and Fairlight.

Family Snapshot

One of few narrative songs by Peter Gabriel tells the story of a political assassin. The lyrics are based on the book An Assassin’s Diary by the near-murderer Arthur Bremer who shot and wounded George C. Wallace, governor of Alabama, in 1972. Other aspects of the lyrics also parallel the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The song develops from a calm vocal section accompanied only by a piano into a driving rock rhythm in which the congenial saxophone plays a big role, until the firing of the shot (“and I let the bullet fly…”) introduces the introspective closing section that provides an insight into the soul and troubled childhood of the assassin. In the end it is hard to believe that this variety of moods and sophisticated drama structure are only four and half a minute long. This highly dramatic song would be a fixture in Gabriel’s live repertoire. It was the first time Peter Gabriel used the electric Yamaha CP-70 piano his former band mate Tony Banks liked so well (and which would take a central place in Gabriel’s keyboard setup). Gabriel used of different synthesizer sounds to slowly build the tension, which shows how familiar he had become with the means of music technology.

And Through The Wire

This song seems to be a close relative to I Don’t Remember: The melody does not change too much; its simplicity is charming yet also rather tiring, the verse is kind of aimless. Technical refinements are still plentiful, yet not quite as frequent as elsewhere. The tambourine sort of breaks the rule of “no metal” drumming. The song becomes more aggressive towards the end; this is when it works best.

Games Without Frontiers

Cheesy drum machine sound introduces the big hit single on Melt. Kate Bush breathes her “jeux sans frontières” and a totally unambitioned guitar adds itself to it. To top it all off: filtered, peculiar synthesizer sounds. And still Games Without Frontiers is totally captivating from the beginning. The song shows both the new approach to song-writing based on drum machine patterns and the excellent yet simplified production. The bombastic and possibly still Genesis-influenced sound that Gabriel occasionally brought to bear on his first to albums (e.g. Moribund…, Here Comes The Flood, White Shadow) has vanished. Near the end the electronic drumbeat is loosened by well-placed fills while the treasure chest of sounds opens again and peculiar exciting sounds emerge.

The lyrics are ostensibly all about a pan-European TV game show known in Germany as Spiel Ohne Grenzen (German for “Games Without Frontiers”), as Intervilles in France and as It’s A Knockout in the UK. The international version of this programme was actually called Jeux Sans Frontières. In it, contestants from different cities dress up in silly costumes and “compete” with each other in silly games. Gabriel addresses the childish behavior the adults show in the game show. Behind this façade, however, there is criticism of nationalism and war, especially the Cold War: “Games without frontiers, war without tears” may be a chiffre for the East-West-conflict. Gabriel would underline the antimilitaristic stance of this song by his introductions. Games Without Frontiers became Gabriel’s first Top Ten hit as a solo artist. In the UK charts it reached #4, the best position of a Gabriel single (six years later Sledgehammer would equal that record). In the US Games Without Frontiers reached #48.

Not One Of Us

The beginning sounds as if you had caught Gabriel practicing his voice – a neat little imperfection that brings on a gripping intro. Urgent guitar and a mixture of electronic sounds from both the synthesizer and the Fairlight along with distorted shouts. Again a creepy mood builds and continues into the verse. A quick drum rhythm carried mainly by the toms drive this song on. The chorus sounds more like a mob shouting slogans than like vocals. This seems to be the intention of the lyrics: “You’re not one of us” is the tell-tale sign of xenophobia or at least differentiation from the Other.

Lead A Normal Life

A two-note rhythm on the xylophone and a couple of piano notes from the Yamaha CP-70 lead into this song. The friendly beginning is soon disturbed by distorted voices in the background, and indeed the song that follows resembles passages from Humdrum or In The Flood. The lyrics are brief, not immediately obvious and seem to point at life in a psychiatric clinic: The beautiful park, no knives, only spoons and someone‘s wish “we want to see you lead a normal life” – and the words “normal life” are distorted which brings out the question what is normal anyway. A simple yet convincing song that makes you think.

Biko

An African mourning chant begins the final track; its simple structure and its sparse instrumentation is exemplary for the solo qualities Gabriel shows on this album: From simplicity comes clearness, from clearness comes atmosphere. The melody and harmonies do not change very much in this song. The focus is on the atmosphere and the mood. Both of them are strong, and you will find it very difficult to withstand the spell cast by this song. Lyrics like “when I try to sleep at night I can only dream in red” are as moving as the simple “the man is dead, the man is dead” that sounds like an archaic wail of mourning. The song tells the tale of South African civil rights activist Steven Biko who was killed on behalf of the government and turns this into an artistic but nevertheless massively political indictment of the South African apartheid regime that was in power then.

Ever more instruments join in as the song progresses – even bagpipes! Gabriel later explained that he always felt bagpipes had something very African about them. Almost prophetic are the words about the fire that cannot be blown out and the eyes of the world that are watching. This song made Peter Gabriel a political rock star, a role he would fill out actively in the years to come, particularly if you consider picking up elements of music from other continents political. Biko became another fixture in Gabriel’s live set (usually at the end). In 1989 the Simple Minds recorded a cover version of Biko that stayed close to the original.

Gabriel’s record company in the U.S. were not very happy with this complex work full of different moods and new sounds and declined to release it: Too artsy, too esoteric – nothing for the U.S. market, they thought. Only when Games Without Frontiers raced up the charts everywhere did they try to buy back the distribution rights. But by then Charisma Records had struck a deal with Mercury Records, making Melt the only Peter Gabriel album to be released on this label. It reached #22 in the U.S. charts (PG1 "car" reached #38, PG2 "scratch" went to #45). In Germany the album topped at #9, while Games Without Frontiers became a Top 40 hit at #36. In June 1980 the record even reached the pole position in the UK album charts.

Melt put Peter Gabriel firmly on solid ground. All the new technological opportunities gave him new ways to express himself and widely expanded the range of sounds available. And this was just the beginning of the experiments in sounds – as a consequence the focus would move from melodies and song structures to sounds, which made some songs more exciting for the producer than for the listener. The effort that was put into producing the album paid off, though: With the exception of some parts Melt sounds hardly dated and certainly not like the typical 80s plastic sound.

Peter Gabriel’s third solo record definitely is one his classic albums, marking the beginning of a very successful and productive phase that brought us PG IV (aka Security), the Birdy soundtrack and So. Four records in six years – today his releases have become a lot rarer. When the Rolling Stone put together their list of “100 greatest albums of the 1980s” in 1989 it came in at #45. Eleven years later Q magazine counted Melt among the “Top 100 greatest British albums” at #53.

by Jan Hecker-Stampehl

translated by Martin Klinkhardt

The return favour album: Peter Gabriel's songs are covered by other artists.