Anton Bruckner is said to have been scared of writing his 9th symphony some 120 years ago, seeing that their ninth had been the last symphony for a number of composers, not least Ludwig van Beethoven. Bruckner was right, his ninth symphony was to be his last. This is something the latter day "Ant[h]on[y] B.", whose new offering Five we are considering in these lines, needs not worry about. For one thing, he is unlikely to write a body of music that might match even the loosest criteria for a symphony. When asked about the formal structure of his pieces in the interview he gave genesis-news.com on February 23, 2018, he replied: "I don't think about that too much. I do what I do and hope to carry other people with me." Considering the way he counts down his orchestral albums (except for The Wicked Lady), the seventh might be the last. Unless he does an eighth album, Zero, an album-length tacet a la John Cage. Those among us who are favourably disposed towards Tony Banks' music may have to worry about something else altogether: If he keeps up the interval of seven years between orchestral albums, he is going to release One aged 96. Bruckner died at 72, and let's not mention Beethoven whose final curtain dropped at 56.

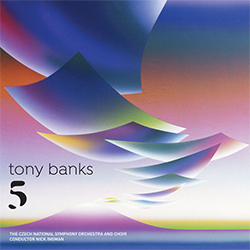

Let us turn to the music. The prologue, or rather prelude, is well-known: In 2014, a piece of music by Tony Banks premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival. It had been commissioned by the Festival and had the slightly clumsy title Arpegg. The title was all the more awkward because arpeggi are not the central element, at least of the finalized version. Arpegg was reworked and became Prelude To A Million Years, the longest and the opening piece on the album. Tony also revealed in the afore-mentioned interview that the album closer, Renaissance, was the last bit written, though it used something Tony had recorded 30 years ago as a musical idea. The other pieces a brand new. As on SIX Pieces For Orchestra, Tony entrusted the jobs of arranger and conductor to the same person, Nick Ingman. Ingman's field of work is the “commercial music field” (which is not just commercials). Ingman also co-arranged Stephin Merritt's The Book Of Love for Peter Gabriel. While the opening track takes its title from a 1933 book without words by American artist Lynd Ward (allusions to literature not being rare in Tony's oeuvre), the other four pieces refer to times of the day: Reveille to the morning, Ebb And Flow to noon, Autumn Sonata to evening and Renaissance to the night. A marked contrast – a million years versus a colourful day. There are a number of spots for soloists, though their solos are not the focal parts of the piece. Tony plays the piano on all tracks, as he did on three pieces on Seven. The piano was recorded first. Combined with clicktracks it was used as a guideline for the musicians, whose parts were not recorded a tutti but voice by voice and section by section. This way of working, though it may by the norm in popular music, is less frequently employed in classical recordings. A real innovation over the preceding albums is the use of a choir Nick Ingman suggested for three pieces. The choir does not sing any lyrics but only vocalises; their timbre really adds to the sound.

Let us turn to the music. The prologue, or rather prelude, is well-known: In 2014, a piece of music by Tony Banks premiered at the Cheltenham Music Festival. It had been commissioned by the Festival and had the slightly clumsy title Arpegg. The title was all the more awkward because arpeggi are not the central element, at least of the finalized version. Arpegg was reworked and became Prelude To A Million Years, the longest and the opening piece on the album. Tony also revealed in the afore-mentioned interview that the album closer, Renaissance, was the last bit written, though it used something Tony had recorded 30 years ago as a musical idea. The other pieces a brand new. As on SIX Pieces For Orchestra, Tony entrusted the jobs of arranger and conductor to the same person, Nick Ingman. Ingman's field of work is the “commercial music field” (which is not just commercials). Ingman also co-arranged Stephin Merritt's The Book Of Love for Peter Gabriel. While the opening track takes its title from a 1933 book without words by American artist Lynd Ward (allusions to literature not being rare in Tony's oeuvre), the other four pieces refer to times of the day: Reveille to the morning, Ebb And Flow to noon, Autumn Sonata to evening and Renaissance to the night. A marked contrast – a million years versus a colourful day. There are a number of spots for soloists, though their solos are not the focal parts of the piece. Tony plays the piano on all tracks, as he did on three pieces on Seven. The piano was recorded first. Combined with clicktracks it was used as a guideline for the musicians, whose parts were not recorded a tutti but voice by voice and section by section. This way of working, though it may by the norm in popular music, is less frequently employed in classical recordings. A real innovation over the preceding albums is the use of a choir Nick Ingman suggested for three pieces. The choir does not sing any lyrics but only vocalises; their timbre really adds to the sound.

The Prelude begins and ends in C major. An introduction resembles the earliest stages of dawn, though it is gloomier than Edvard Grieg's Morning Mood from Peer Gynt. A melody shapes and the main theme of the piece begins to reveal itself from 1:38 onwards before it appears in F major in 2:07. A lightfooted arrangement with flute arpeggi is suddenly interrupted by a doubled Dies Irae bit before the oboe comes in at 3:46 in B major which moves into a suspense-packed bit in C sharp minor and introduces a side theme in 4:16. The main theme returns and is raised to a brilliant catchy form from 5:09. A couple of staccatos and modulations of the side theme later the piece is roughly repeated from the introduction to the brilliant main theme. The latter does not have the last word as the piece returns to the gloom of the introduction.

The Prelude begins and ends in C major. An introduction resembles the earliest stages of dawn, though it is gloomier than Edvard Grieg's Morning Mood from Peer Gynt. A melody shapes and the main theme of the piece begins to reveal itself from 1:38 onwards before it appears in F major in 2:07. A lightfooted arrangement with flute arpeggi is suddenly interrupted by a doubled Dies Irae bit before the oboe comes in at 3:46 in B major which moves into a suspense-packed bit in C sharp minor and introduces a side theme in 4:16. The main theme returns and is raised to a brilliant catchy form from 5:09. A couple of staccatos and modulations of the side theme later the piece is roughly repeated from the introduction to the brilliant main theme. The latter does not have the last word as the piece returns to the gloom of the introduction.

The first sounds of Reveille unsettle the listener. Is there really a musician playing fast arpeggi in G minor on an orchestra instrument (an idiophone, e.g. a xylophone), or has this pattern, that is joined by more and more (real) instruments, been created electronically? A solo trumpet comes in at 0:46. It dominates the piece and introduces the main theme in 1:24; the music is once more in lazy/uninspired or carefully chosen C major. The choir comes in at 1:54 and strengthens the wall of sound with its harmonies as a second trumpet joins the first. The fast basic rhythm breaks off, and a calmer part begins at 2:28 with the piano shaping the structure. The melody uses material from the main theme. The number of musicians drops to chamber music level in 3:56. A brief intermezzo by a string quartet and oboe leads into the reintroduction of the arpeggiated basic rhythm from 4:16 onwards – the first part reprised, ritardando and another calm part from 5:48 moving to E flat major in 6:10. Prominent use of glockenspiel (also used in Seven) in 6:50; this briefest piece on the album has a C major coda from 8:25.

The key is lowered to B major towards noon for Ebb And Flow, but it does not stay there long. The first main theme, introduced at 0:32 in E major, undergoes exciting modulations and a BACH motive at 1:13 (G flat, F, A flat, G). The strings play a fast staccato rhythm from 1:39 while soprano saxophone and oboe solo over it. Though we have no intention to completely dissect the piece further, we would like to mention the prominent role of the harp and a vibraphone that accompanies a string quartet (from 5:18). The sudden harmonic changes (e.g. at 1:08 or at 5:42) are simply delightful. From 11:07 the piece feels like the emotional climax of a Star Wars classic (the declining fourth reminds us of John Williams' main theme from Star Wars), before the music ebbs off at 12:06 and repeats the first theme of the piece – in E flat major this time – as a coda.

The key is lowered to B major towards noon for Ebb And Flow, but it does not stay there long. The first main theme, introduced at 0:32 in E major, undergoes exciting modulations and a BACH motive at 1:13 (G flat, F, A flat, G). The strings play a fast staccato rhythm from 1:39 while soprano saxophone and oboe solo over it. Though we have no intention to completely dissect the piece further, we would like to mention the prominent role of the harp and a vibraphone that accompanies a string quartet (from 5:18). The sudden harmonic changes (e.g. at 1:08 or at 5:42) are simply delightful. From 11:07 the piece feels like the emotional climax of a Star Wars classic (the declining fourth reminds us of John Williams' main theme from Star Wars), before the music ebbs off at 12:06 and repeats the first theme of the piece – in E flat major this time – as a coda.

The Autumn Sonata introduces its cantabile theme in E major without any introduction. Stylistically it resembles Phil Collins' Disney soundtracks. Since a sonata is a piece of chamber music, this piece here is not really a sonata (the orchestral variant is called a symphony) and does not contain any elements of the sonata form. It does, however, match the literal translation of sonata as a “sonorous piece”, and it is certainly that. The theme in E major continues in D flat major with some typical Banks modulations. There is a charming trumpet solo part (from 2:38), and the excitingly mystical development turns positively quaint from 3:48 onwards. The trumpet theme that sounded so merry three minutes ago is repeated at 5:38 in completely different harmonies. The dramatic finale is foreshadowed at 6:10 before the cheerful part in D flat major returns. Then a dramatic buildup (with the choir from 8:30 onwards) before the piece ends serenely.

Renaissance has a number of themes and it makes good use of the choir. Like an early Genesis song (Stagnation comes to mind) it combines very different parts. As in the Prelude, the piece begins with a long low C. Strings and oboe embark on a monody in an unusual diatonic scale before a strong crescendo on an augmented chord makes the listener freeze – … Change of scene: A rich melancholic elegy that could have been written by Nino Rota makes every fibre melt. It is presented by strings, choir and a solo instrument we found impossible to identify. Its sound is somewhere between a comb, a muted trumped, soprano saxophone and Uillean Pipe. The piece becomes quite majestic from 2:54. The 30 seconds from 3:16 onwards may be kitsch to some, while others may consider it the highlight of the album. The spooky introduction is repeated at 5:21 before the piano begins the finale with a new theme in a strong forte that leads to the most dramatic conclusion of all the pieces on the album; the majestic theme returns and the choir presents its augmented chord (A flat, C, E) across the radiant final chord in A flat major. Tony has used similar choir sounds as an augmented chords (two major thirds on top of each other) more than fourty years ago with his mellotron in Los Endos when the piece quotes the alienated motive from Dance On A Volcano before it hurtles into the grand finale.

Renaissance has a number of themes and it makes good use of the choir. Like an early Genesis song (Stagnation comes to mind) it combines very different parts. As in the Prelude, the piece begins with a long low C. Strings and oboe embark on a monody in an unusual diatonic scale before a strong crescendo on an augmented chord makes the listener freeze – … Change of scene: A rich melancholic elegy that could have been written by Nino Rota makes every fibre melt. It is presented by strings, choir and a solo instrument we found impossible to identify. Its sound is somewhere between a comb, a muted trumped, soprano saxophone and Uillean Pipe. The piece becomes quite majestic from 2:54. The 30 seconds from 3:16 onwards may be kitsch to some, while others may consider it the highlight of the album. The spooky introduction is repeated at 5:21 before the piano begins the finale with a new theme in a strong forte that leads to the most dramatic conclusion of all the pieces on the album; the majestic theme returns and the choir presents its augmented chord (A flat, C, E) across the radiant final chord in A flat major. Tony has used similar choir sounds as an augmented chords (two major thirds on top of each other) more than fourty years ago with his mellotron in Los Endos when the piece quotes the alienated motive from Dance On A Volcano before it hurtles into the grand finale.

Openminded friends of music are urged to listen to this album at least two or three times. The first run-through did not achieve more than striking out all the expectations I had from this album. When I listened to it for the second time I began to appreciate the richness and balance of the album. Now, after a few days, I rank it Tony's best album (along with A Curious Feeling). I agree with what Tony said in an interview with a Czech magazine: It is his best classical album so fast. Seven had lots of good ideas but also some lengths, and SIX had left me completely cold. Whether these improvements are due to Tony developing as an artist of due to personal and technical changes for this project is a question I do not care about much right now. There are not many album with new music being released from the Genesis camp. When they are and when they show real development (as in this album) and do not stand in the shadows of previous glories or show the artist copying himself, there is all the more reason to congratulate Tony Banks for it!

Author: Andreas Lauer

English by Martin Klinkhardt

Phil Collins Debutalbum became a classic of the 80ies and is probably his best album to date.

Review available