Some two years had passed after his time in Genesis before Gabriel dared re-enter the music business he had left so abruptly that it seemed like a flight. He apparently found he could not do without it and so, after a few tentative attempts, he returned to the studio in 1976. The album he wrote became the founding stone of his solo career. It turned out a beginning that was at the same time remarkable and „muddled“.

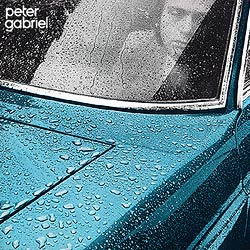

The first four solo albums Peter Gabriel made would not bear a title but simply be labeled peter gabriel. He explained that his albums should be considered like numbers of a magazine that do not have a title of their own either. Since this approach led to difficulties for dealers and fans people came to use unofficial titles for the albums. Because of the automobile on the cover the first album has been dubbed Car.

In the beginning of his solo works Gabriel was still trying to find his way. He recorded his first album in Toronto, far away from his home in England, from Charterhouse and everything that linked Gabriel with the old band. His time in Genesis had, of course, had a lasting influence on him and cast the foundation for his reputation as a singer, songwriter and performer. Genesis' music meandered between folk, rock and classical while the lyrics were usually tricky, pun-filled fairy tales. Gabriel has always enjoyed telling obscure stories and thoughts in wide-screen format there.

In the beginning of his solo works Gabriel was still trying to find his way. He recorded his first album in Toronto, far away from his home in England, from Charterhouse and everything that linked Gabriel with the old band. His time in Genesis had, of course, had a lasting influence on him and cast the foundation for his reputation as a singer, songwriter and performer. Genesis' music meandered between folk, rock and classical while the lyrics were usually tricky, pun-filled fairy tales. Gabriel has always enjoyed telling obscure stories and thoughts in wide-screen format there.

Now, wanting to turn away from the art rock Genesis made, he approached other styles, though one occasionally feels he is looking for contact. Almost all the songs follow the conventional pattern of verse-chorus-verse, which is a marked contrast to the meandering structures of Genesis songs. Gabriel also uses elements of hard rock rather than classical music (e.g. in Modern Love), and he would continue to make use of them, particularly live, well into the mid-80s.

The album was led and strongly influenced by its producer, Bob Ezrin, who rather belongs to the bombast side of rock (Alice Cooper, Kiss). Musically it is rich in arrangements that hail from guitar mainstream but also in unexpected effects. Strings and a brass group help give the album a big, lofty, expansive, in short: a bombastic sound that tries to bridge the gap between idiosyncrasy and catchiness. Gabriel obviously leaves many things to his coworkers - either because he is insecure or because he is curious.

The album has some beautiful timeless songs that have not aged at all. One of these is obviously Solsbury Hill (a comparatively simple production), the sensitive Humdrum and perhaps the weird and wonderful Moribund The Burgermeister. Excuse Me on the other hand is a rather bizarre a capella / Barbershop experience. Yet other songs such as Down The Dolce Vita and Waiting For The Big One present themselves as the archetypical rock song with the big approach. These are sounds one would not necessarily have associated with Gabriel, and indeed they hardly ever recur in the thoughtful profundity of his later songs. And if you listen to the album version of Here Comes The Flood which is mainly a vehicle for the playfully elegiac guitar solos so beloved by blues rock song writers in the late 70s you will find it very hard to believe that this is the same song as the melancholy, measured song Peter Gabriel would perform on the solo piano for almost every show since his first solo tour.

As far the lyrics are concerned, Gabriel still writes stories as weird as in his times with Genesis, but also introspective lyrics, which is a first for him. The words to his songs are, however, still rich in puns that require careful interpretation.

The band that recorded Gabriel’s first album is made up of several musicians who would accompany him in years to come and also leave their mark in his work: Robert Fripp would be the producer of Gabriel’s next album, Larry Fast is there, Gabriel’s the long-term synthesizer teacher, and so is the bass player Tony Levin who has been a good friend of Peter’s ever since.

Odd bubbling and beating sounds mark the beginning of the album, but when the chorus begins it all turns into a solid rock song with lots of pathos. It is the story of a disturbing case of a whole town catching St Vitus’ dance. Not bad as a beginning, and the grotesque qualities leave quite a lasting impression.

The second song is the most enduring hit of Gabriel’s whole solo career. It begins in an unusual but driving 7/8, almost like a folk song, before it unleashes its power and ends in hunted vocal eruptions. Gabriel addresses feelings of doubt, loneliness and changes in life, topics that are quite likely to have risen in him when he left Genesis.

The song with the most bang on the album. Lots of power and a good deal of aggression are brought to bear on lyrics rich in innuendo that talk about love without feeling, desire and unfulfillment. Though the song was released as a single it soon dropped from the standard repertoire.

Playful, silly, comedic – all this makes up this weird barber shop song. The lyrics are enigmatic rather stream-of-consciousness than narrative. The song creates a peculiar relaxed mood that seems a bit fishy. It is, however, a wonderfully eccentric introduction for Humdrum and its brooding mood.

The most depressed piece on the album. Gabriel uses fantastic word imagery to describe the eponymous monotony and torpor. It begins with piano sounds that have an unusual stereo distortion. Other means used are Latin-American motives carefully placed wrong, melancholy acoustic guitars and thick blankets of synth strings. This song points ahead to how Gabriel would later combine musical and lyrics expression.

Back in the days of vinyl this would be the first song on the second, altogether weaker side of the record. The arrangements are just too pretentious and too contrived. Slowburn comes with a whining lead guitar and a strong beat. It is a bizarre love song complete with heartache. Fast changes in the speed, rattling drum fills and glam rock borrowings are meant to intrigue, but all they do is to kill of any interest in the words. There is rarely any link between the content and the music.

A blues, and it is celebrated as such from the counting in and loose piano runs to the lofty choir finale. Lots of drama, lots of big opera. In between, with a disturbed voice, is Gabriel’s punning description of the wait for the big one. It illustrates the futility and emptiness, though the musical devices are used to a degree where the become almost comical.

And here is a full Wagner orchestra running over the listener at full speed. It retains the energy and continues as a rock song. The lyrics express a certain enigma and futility again, but do so with a grand gesture. Lots of gimmicks in the arrangements (such as the general pause in the middle part) vie for the listener’s attention. It would take Gabriel more than three decades to be able to create suspense by these means (in his Scratch My Back project – with Bob Ezrin again as a co-producer). Numerous musical turns convey the mood of the lyrics less successfully than Gabriel may have hoped for.

Gabriel himself would later call this version of the song overproduced. Unfortunately, the studio team could not think of anything else but to turn the eschatological visions of inner torpor into a catchy anthem by the usual devices of bluesrock (dramatic changes in dynamism, elegiac guitar solos and beating tambourines).

The album is a first attempt for Gabriel try and build a career as a solo artist. He has not quite found his feet yet, but the large potential is evident. If you are keen to discover the music of Peter Gabriel you may find this one of the more difficult entry points.

The return favour album: Peter Gabriel's songs are covered by other artists.

Double-CD with both, Scratch My Back and ... And I'll Scratch Yours in digipak format