It is 1985: The middle of the 80s, and pop music reaches new heights. Bands like Duran Duran, Depeche Mode, a-ha and The Pretenders write new classic songs. Some older dinosaurs have left us by force, e.g. Led Zeppelin, or experience a renaissance, like Eric Clapton. There are bands that change their style radically, such as Queen and Genesis, who appropriate the 1980s pop, and Phil Collins brings out No Jacket Required, an album bursting at the seams with hit singles. Enter Mike Rutherford of Genesis. Two years before, he and his band mates brought out a great album simply called Genesis and surprised everyone with the extraordinary single Mama for which he had developed the remarkable drum machine rhythm.

Genesis is not enough for him, and, as Mr Rutherford puts is, he need a “breath of fresh air”. After two solo albums that were no failures but not successful either Mike decides to put together a new team for his song ideas. He wants to work with other composers – the term “songwriters’ collective” goes back to the early days of genesis. Mike also realized that he is not a good singer and could use some support in that department.

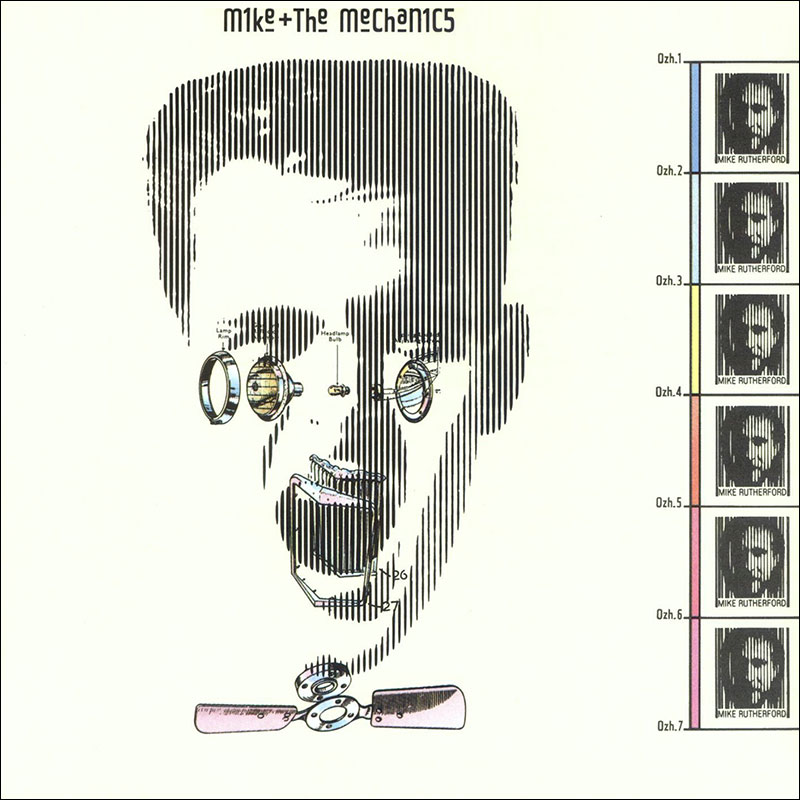

Mike is going to write the songs for this and the next three albums with B.A. Robertson and Christopher Neil, who also produces this first album. The band name was probably spawned by the basic idea of the project, but it is peculiar and weird rather than cool in a decade focused on coolness.

Mike + The Mechanics were born. The image of a mechanic will resurface on many forthcoming album artworks.

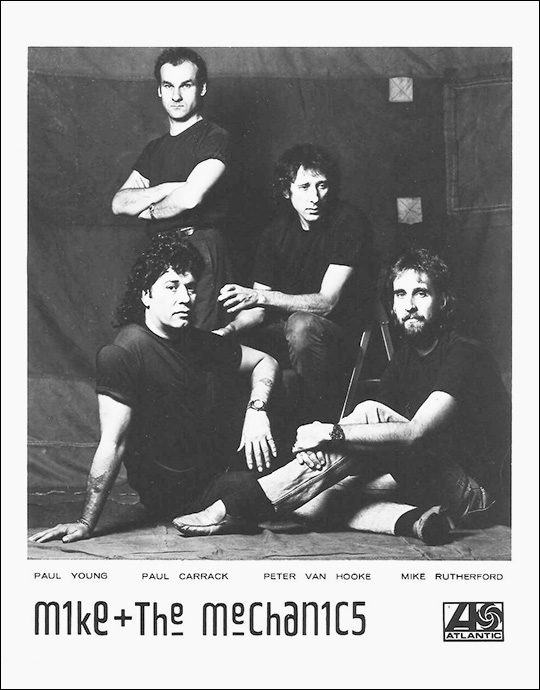

Mike Rutherford has three (actually, four) singers sing his new songs – on an album that has only nine songs in total. Paul Carrack and Paul Young will become the core singers; both have already made a name for themselves. The line-up of Mike, both Pauls, drummer Peter van Hooke and keyboarder Adrian Lee would remain unchanged up to and including their third album, Word Of Mouth.

Mike Rutherford has three (actually, four) singers sing his new songs – on an album that has only nine songs in total. Paul Carrack and Paul Young will become the core singers; both have already made a name for themselves. The line-up of Mike, both Pauls, drummer Peter van Hooke and keyboarder Adrian Lee would remain unchanged up to and including their third album, Word Of Mouth.

The album artwork is a bit bland and inconclusive. It does not reveal anything about what music the listener may expect. A keyboard hovers in this atmospheric intro that develops into a bombastic mid-tempo pop/rock song. Paul Carrack sings this first song, which was also used in the science-fiction movie Choke Canyon (a.k.a. On Dangerous Ground). The production is rich, cool and sounds rather technical, in a word: like a typical 1980s production. Silent Running gives you an appetite for more, and you won’t be disappointed.

The first highlight is chased by a second. All I Need Is A Miracle has a classic catchy chorus – you can’t get it out of your head, and it as simple as it is brilliant. Opinions on the lyrics of “all I need is a miracle, all I need is you” may differ. It still is a great, positive song that gets everybody going at the Mechanics shows. Paul Young sings it with ease and strength.

The third song, the third singer and, we must say, the first shift in quality. Par Avion is a ballad sung by John Kirby that has nothing to offer. A Genesis drum machine makes up the basis of the song. Lyrics like “here comes the night, here comes the dreaming of you” do not exactly prompt the listener to return to this song, which is a pity after such a strong beginning.

Hanging By A Thread begins with a fast beat that jarringly resembles the sound of gun shots before it almost explodes. Paul Young adds energetic vocals to this powerful song. Turn up the volume for the beautiful, purely instrumental and melodic middle eight.

The song after that, I Get The Feeling, marks the next stylistic break. The arrangement is less lush. Paul Carrack sings the song with an organ in the background. The fanfare-like keyboards might as well be real horns. A fine song that brings variation and soul into the album.

Take The Reins is another harder track, and you get the idea how the singers have divided their territories. Paul Young sings the rock songs (like this one), and Paul Carrack takes over the softer part with lots of Blue-Eyed Soul in his voice. There is a crisp and clear guitar solo, too, and before your inner eye you see a typical axeman of the 80s shake his instrument, no, not the wild hair.

Take The Reins is another harder track, and you get the idea how the singers have divided their territories. Paul Young sings the rock songs (like this one), and Paul Carrack takes over the softer part with lots of Blue-Eyed Soul in his voice. There is a crisp and clear guitar solo, too, and before your inner eye you see a typical axeman of the 80s shake his instrument, no, not the wild hair.

The second ballad of the album, sung by John Kirby again, is a complete failure. You Are The One is an anthemic song that fades out in the middle of the vocals so that it cannot leave a favourable impression. A-ha’s song by the same title is much better.

Next up is the secret highlight of the album: A Call To Arms developed during the sessions for Genesis’ self-titled album. The dramatic, gloomy song is sung by Paul Carrack with Gene Stashuck. Solemn keyboards kick off the song. A stomping beat and Gene’s vocals evoke the call to arms. The loftier, less gloomy part features Paul Carrack and a wonderful backing choir. Of course you are bound to wonder what this song would have sounded like with Phil Collins, but it would not have fit on the Genesis album. Here is where the song really comes alive. Unfortunately, this song has not proper ending either and simply fades out.

The last track of the album is called Taken In. The ballad is sung by, yes, Paul Young with a pleasant melody. The arrangement is kept quit simple, and the sensitive saxophone actually contrives to be not kitschy.

A remarkable album ends after nine songs, most of which are interesting or excellent. It is most peculiar that the ballads should be the weak songs, for Mike had already proved that he is good at writing ballads, too. The “dingi-dingi-ding” guitar sound that was to become Mike’s trademark cannot be heard yet on this album, though it will turn up with a vengeance on Genesis’ next album (particularly the title track Invisible Touch) – and when the Mechanics start to play Living Years they would not work without this signature sound. But that’s another story.

Double-album with new versions of Genesis classics and guest musicians such as Steve Wilson, Nik Kershaw, John Wetton, Steve Rothery or Simon Collins